Norfork resident Steve Wilson can sympathize with the young soccer players and their coach recently trapped in a cave in Thailand for days.

More than five decades ago, Wilson watched his three buddies each put on a wet suit top, a mask and flippers and then disappear into the water inside a cave in rural Arkansas.

Now it was his turn and he was nervous. None of them had any experience scuba diving, but they had been given a five-minute crash course that afternoon in 1965 and told it was the only way to escape from the cave, which had flooded during a rainstorm, trapping them inside. So Wilson, then 20, dove in, with one Navy diver in front of him and another behind him, feeling his way along a rope underneath the pitch-black water.

Wilson told The Washington Post he was on the verge of panic the entire time. He says the 30-minute trip seemed like it took hours. He could barely see the diver leading the way, and he was concerned about trying to breathe normally under the water. He says he didnt want to mess up and cause harm to himself or cause his rescuers any more problems.

Wilson told the newspaper he doesn’t think the danger those young soccer players and their coach have been in can be overemphasized.

Wilson, a retired director of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, says he and three friends all experienced cave explorers went on a weekend adventure, tracing a stream from Arkansass Rowland Cave to Blanchard Springs Caverns in Stone County.

Wilson, then a wildlife management major at Arkansas Tech University, set out with the other spelunkers, who ranged in age from 19 to 42, on a Friday afternoon with bologna sandwiches, water and other supplies, including lights and an inflatable raft. He says they started in Rowland Cave, a known tourist spot, following the stream toward the caverns, which had not yet been developed by the U.S. Forest Service.

He says they waded through the water sometimes ankle-deep, other times up to their waists unaware that it was pouring down rain outside the cave.

On Saturday, they ran into a rock pile cutting off their path to the caverns, and they had no time to search for another way through, so they turned around.

By Sunday, they had reached the mouth of the cave where they had entered but the water was high and they had no equipment to help them swim out. So the men cold, wet and tired pitched a tent a crude structure built from their rubber raft and some ponchos they had packed to keep themselves dry. Their plan was to burn candles, dry out, warm up and wait for the water to recede.

But they had no idea how long it would take and whether they could make it that long.

Wilson says the men still had water to drink but had very little food left to eat; they assumed they could make it days, maybe weeks, but their leader was diabetic, so medication was also a concern. Plus, he says, the cave was damp and cold, averaging about 56 degrees inside, so they worried about getting sick. Death, however, was not a consideration for the young and adventurous crew.

The four started a rotation three of them would sleep and one would stay up and watch the water level to determine whether it was starting to recede.

Wilson says it was just a matter of waiting.

He says he and the others were also trying to imagine what was happening outside in the rest of the world whether anybody was looking for them.

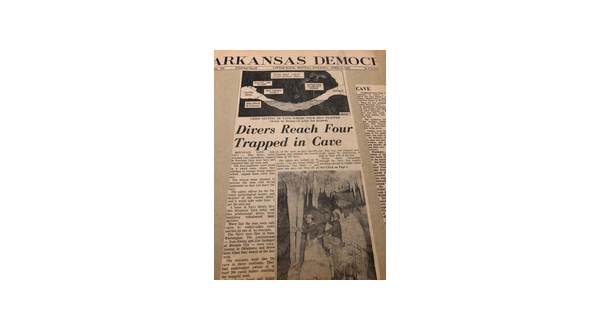

Wilson says another friend and veteran cave explorer who was not able to accompany them that weekend knew where the men had gone and knew the cave would probably be flooded from the rain, so he reported the situation to authorities. Local volunteers tried to rescue them, then divers from the U.S. Navy and the National Speleological Society came to help, according to news reports from that time.

Back home in Morrilton, Wilsons wife, Jo, had learned her husband was trapped by floodwaters.

The newlyweds could not afford a phone, so word had been sent to a neighbor, who told Jo something was wrong. Jo Wilson, a 21-year-old schoolteacher, rushed down to the phone company to use a pay phone to call for details about her husband. She says then, she made the long drive toward the caves with all sorts of things running through her head.

When she got there, she says, she joined Wilsons parents, who were surrounded by other families, friends and reporters all waiting for the men to emerge.

According to an April 5, 1965, article from United Press International: Members of the Navy Deep Sea Diving School and the National Capitol cave rescue team both in Washington, arrived early today at the site of the remote cave in the foothills of the mist-shrouded Ozark Mountains. They immediately began a search for the spelunkers. It added that the men included two seasoned cave explorers, one of them Hugh Shell who has diabetes. Shell, 42, a bookkeeper from Batesville, Ark., was said to have a three-day supply of medicine with him. The other three, all college students, were identified as Mike Hill, 19, a student at Arkansas College, and Steve Wilson, 20, a student at Arkansas Tech in Russellville.

Wilson says he was on watch that Monday when he heard a loud noise, which turned out to be a diver entering the cave. He said the diver handed him a rope and told him to secure it. The men, with help from the divers, would use it to find their way out of the cave.

He says he was relieved. He woke his buddies up and told them what happened, that it looked like divers would rescue them. Everybody was elated to know that the young men were finally going to be rescued.

Wilson says it took about an hour per person each time, one of his buddies would suit up, then, with a diver in front and one behind, would inch along the rope under the water until he made it to land.

Wilson was the last one to be rescued he says the divers told him that since he was the smallest, he would not need his buddies to help him put on the gear.

As he reached land, he says, his wife and his parents rushed toward him, telling him how glad they were that he made it out. It was a joyous moment soon to be marred the diver who had been swimming behind Wilson collapsed on the bank and died. Wilson says the coroner later determined the diver, identified in news reports as 39-year-old Lyle E. Thomas, suffered a heart attack.

The former Arkansas Gazette describe Thomas as a master diver who had been diving 14 of the 22 years he had been in the Navy.

Remembering the tragedy, Wilson says he was totally shocked, and the fact that somebody would end up giving their life to save theirs was an awful feeling.

Speaking about the incident in Thailand, Wilson says he thinks the rescuers have done a spectacular job, rescuing some children and teenagers who are not even swimmers, much less divers.

WebReadyTM Powered by WireReady® NSI