WABC-TV(NEW YORK) — When Palm Springs police Officer Jose “Gil” Vega, a married father of eight, was gunned down with his partner while they responded to a domestic disturbance call, the 35-year veteran was two months away from his retirement.

WABC-TV(NEW YORK) — When Palm Springs police Officer Jose “Gil” Vega, a married father of eight, was gunned down with his partner while they responded to a domestic disturbance call, the 35-year veteran was two months away from his retirement.

Days after the double killing, Vega’s soft-spoken daughter, Vanessa, 8, addressed a sea of uniformed officers and other mourners gathered at a vigil for her father, 63, and his fellow slain officer, Lesley Zerebny, 27. Zerebny had just returned to duty after giving birth four months earlier.

Vanessa told the crowd it wasn’t her father’s turn to die, but added, “He will be watching us — he won’t ever leave.”

“He was happy with his life,” Vanessa said, adding, “He’s in peace now.”

Vega and Zerebny were two of 159 on-duty officers killed in the country in 2016, according to statistics kept by the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund.

A troubling increase

While officers die in traffic-related incidents more than any other situation, this year, the deaths of officers by guns has climbed to a “troubling” number.

From Jan. 1 to March 30, 2017, 10 on-duty officers were shot dead. From Jan. 1 to March 30 of this year, 20 on-duty officers were shot dead.

“I do worry about these firearm-related deaths,” Steve Groeninger, senior director of communications and marketing at the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, told ABC News. “It’s troubling.”

“It’s too soon to know if it’s a trend,” Groeninger added. “As [the second quarter] plays out and we receive data forms from departments who lost an officer this year, we’ll be able to better assess and quantify.”

In 2017, 46 on-duty officers were killed by guns, according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund. The year before, it was 67, and in 2015, it was 43.

If this year’s pattern continues at its current rate, 2018 could see 80 on-duty police deaths from gun violence.

Former FBI agent and ABC News contributor Steve Gomez called the increase from 2017 to 2018 “disturbing.”

“This is a trend that we are seeing with regard to people acting out, people not having self-control, especially when dealing with law enforcement officers. I think it’s a symptom of both that lack of control and complying with law enforcement and we are now seeing more people who have [behavioral and mental problems] and they have access to firearms,” Gomez said. “That’s a deadly combination.”

“This has been the deadliest year for law enforcement in many, many years [so far],” said former Dallas police chief and ABC News contributor David Brown. While the trend appears to be on the rise this year, Brown said, he added that overall it hasn’t reached the peaks of the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s.

Officers in small towns are just at risk as officers in cities, Brown said. A police officer in urban Pomona, California, and an officer in rural Clinton, Missouri, were both shot dead in the month of March.

An especially big fear now is police ambushes, which Brown said are increasing. The uptick has led to more officers being told to wait for cover and not quickly rush in as often when responding to crisis calls, he said.

“There’s always a high degree of alert among law enforcement professionals,” Groenginer said. “They never know what could be around the corner. They never know when they could be targeted just because they are in a uniform.”

But new solutions for dealing with violence are always in the works.

To help combat the increasing number of ambushes, some officers are using heavier ballistic vests.

“New York has been the leader in this because they added some ballistic material to the police cars, to the windows and doors, because they had officers ambushed in their car,” Brown said.

There are also car manufacturers installing sensors in the back of police cars to alert an officer if someone is approaching from behind while a car is parked, according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund.

Police applications on the decline

“One of the most concerning things is not a lot of people are wanting to be police officers” due to police criticism and heightened dangers, Brown said.

Gomez agreed. He said one official told him departments are “struggling to get qualified candidates to apply” and Gomez thinks it’s partly because of what he calls the “Ferguson effect.”

In 2014, a white police officer fatally shot an African-American teen in Ferguson, Missouri, sparking large-scale protests.

Gomez said Ferguson and similar police shootings have since “continued to impact the perception of law enforcement.”

“Potential candidates entering into law enforcement feel that they don’t have the support of the public and of government officials,” Gomez said.

Jonathan Thompson, executive director of the National Sheriffs’ Association, said that five years ago, there were 100 applicants for every vacancy. That number is down to the low 60s now, he said.

Last year, 34-year-old New York City police officer Miosotis Familia was gunned down while she was sitting in her marked police command vehicle, writing in her memo book.

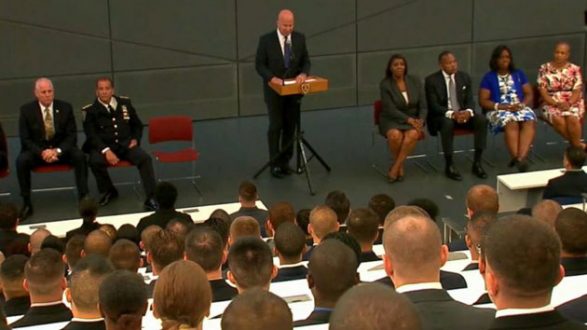

One day after the shooting, the NYPD police commissioner reassured hundreds of recruits at their swearing-in ceremony that they had “absolutely” made the right career choice.

“The work of Officer Miosotis Familia is not finished,” NYPD Commissioner James O’Neill said, telling the recruits that it is their job as cops to finish it.

‘The profession is on edge’

What’s likely contributing to the increase in deadly shootings is some officers are now hesitant to use force in dangerous situations because they feel they no longer have support from the public and the government, Gomez said.

“If you’re hesitant in using force, especially deadly force, then you are putting yourself at a disadvantage in a dangerous situation,” Gomez said.

According to The Washington Post’s database cataloging fatal police-involved shootings, 264 people have been shot and killed by police so far this year. In 2017, 987 people were fatally shot by police, and as of last week, there have been four fewer shootings this year than at the same time last year.

Brown said he thinks there’s a decrease in trust of the government and thus a decrease in trust of law enforcement as well.

“I sense a lot of anger” within officers around the country, Brown said.

Many officers feel they can only trust themselves and their partners, Brown said, “and that is not the sentiment you want for a public servant.”

“I’m really concerned that the ‘us against them’ mentality will take over, which is not healthy for delivering the best police service.”

“The profession is on edge,” he said, “and that is when you make mistakes and overreact.”

The shattered families and friends left behind

“Every one of these fatalities represents a shattered family, a department. Often a community,” Groeninger said.

“Specifically in the rural areas where you tend to have smaller departments and smaller workforces,” Groeninger added. “Not only are you grieving that network that’s been shattered due to the death, [but the loss also takes a] big hit to your workforce.”

In Dallas, where five law enforcement officers were gunned down by a sniper in July 2016, their fellow officers who survived are “still in that anger and blame phase” nearly two years later, said Brown, who was the police chief at the time of the attack. He retired several months later after 33 years with the department.

That sniper attack was the deadliest day for United States law enforcement since 9/11.

In the midst of their grief, officers in Dallas “still have to do their job every day,” and are still dealing with the same criticisms and risks of other officers, Brown said.

“You try to move on to the next call and the next crisis, and it’s increasingly difficult,” Brown said. “It’s not a normal recovery from such a tragedy.”

The ultimate sacrifice

For Gloria Vega, one of the adult children of Palm Springs police Officer Gil Vega who was gunned down in October 2016, the past year and a half since his death has been “a big roller coaster.”

“The first six or eight months were by far my hardest months I’ve had,” she told ABC News. “I was constantly crying myself to sleep. I had a really bad depression and it was really hard to get out of that.”

She said what got her through was her children and her big family because that reminder of her dad — whom she describes as funny, affectionate and always smiling — brought her some comfort.

“I miss him daily,” she said. “I miss his jokes. I miss him laughing. I miss texting him before I go to work.”

Gloria Vega, who has an older brother and an older sister, said her parents divorced when she was young. Her dad later remarried and had another daughter, Vanessa, who was 8 at the time of his death. Gil Vega, a 35-year veteran, died just two months away from his retirement.

Growing up, she said she would always worry if something would happen to him while he was on duty. As she got older, her dad’s safety wasn’t her main worry and it was just “in the back of my mind,” she said.

Gloria Vega said the past few years she’d tell her coworkers, “I’m so glad my dad’s so close to retiring, I’m so glad this is something we don’t have to worry about anymore. … And then it happened.”

His death “broke my heart for Vanessa,” she said, because “as a little girl it was always my biggest fear. And for it to happen to her, it hurt my heart. I was fortunate enough to have him for as long as I did.”

Vanessa “took it really hard” but “she’s in really good spirits,” Gloria Vega said. She had “her moments” and cried, but “she’s really tough.”

Looking back at her father’s years on the force, what sticks with her is the mutual respect between him and those he had arrested.

Gloria Vega said after her father once arrested someone, he drove through a Del Taco drive-thru before heading to jail to make sure he’d have food.

Another time, Gloria Vega and her dad were out at a restaurant when a man he had previously arrested stopped by to talk to them and was so friendly that she was shocked.

She said her father told her it was “because ‘I treated him like a human. Just because I’m doing my job and I have to arrest him, I didn’t have to treat him like he was nothing.'”

“The little things he would do for people, he made a difference,” she said, adding he tried to get other officers to follow his lead.

Gloria Vega said she feels like some people “perceive officers just as a badge.”

“Maybe they forget they have families,” Gloria Vega said. “But they’re just like everybody else. The only difference is my dad went out there … he sacrificed his family, sacrificed us having him, to protect people he doesn’t even know.”

Copyright © 2018, ABC Radio. All rights reserved.