𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨

Floods, Freshets, and the Forgotten Captain

Welcome to Retracing Our Roots as Heather Loftis, Adam Rogers, and Vincent Anderson dive into one of the show’s central themes since its beginning: water. This episode focuses on one river in particular, the White River.

In the early 1820s, the White River Valley endured a series of devastating freshets, or sudden floods, unlike anything settlers had ever witnessed.

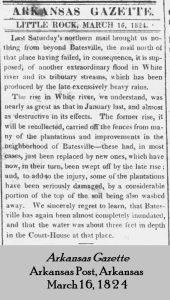

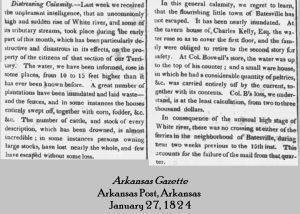

In January 1824, a swift and destructive rise of the White River and its tributaries swept through the region. Entire plantations were submerged. Fences, homes, and crops were destroyed, and untold numbers of livestock drowned. The town of Batesville, still in its early growth, was hit hard. Residents sought safety on second floors, while stores and warehouses were gutted or carried off by the current. Colonel Boswell reportedly lost several thousand dollars’ worth of pelts and furs, an amount equal to about $81,000 today. For nearly two weeks, ferry crossings and mail service were completely halted.

In March of that same year, 1824, another round of heavy rain brought a second freshet that proved nearly as destructive. Rebuilt fences from January were washed away once again, along with vital topsoil that sustained area farms. (Let’s go get our topsoil back! It’s in southeast Arkansas.) As Batesville flooded a second time, three feet of water inundated in the Independence County Courthouse.

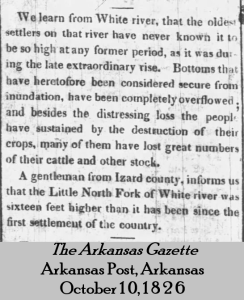

Then in 1826, a third and even more dramatic flood struck. Known as the Pumpkin Freshet, it caused the Little North Fork of the White River to rise sixteen feet higher than any previous level. Even the oldest settlers could not recall anything like it. These successive disasters marked a time of great hardship, but also highlighted the grit and resilience of the early Arkansas frontier.

- - -

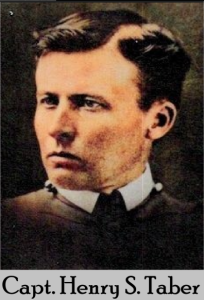

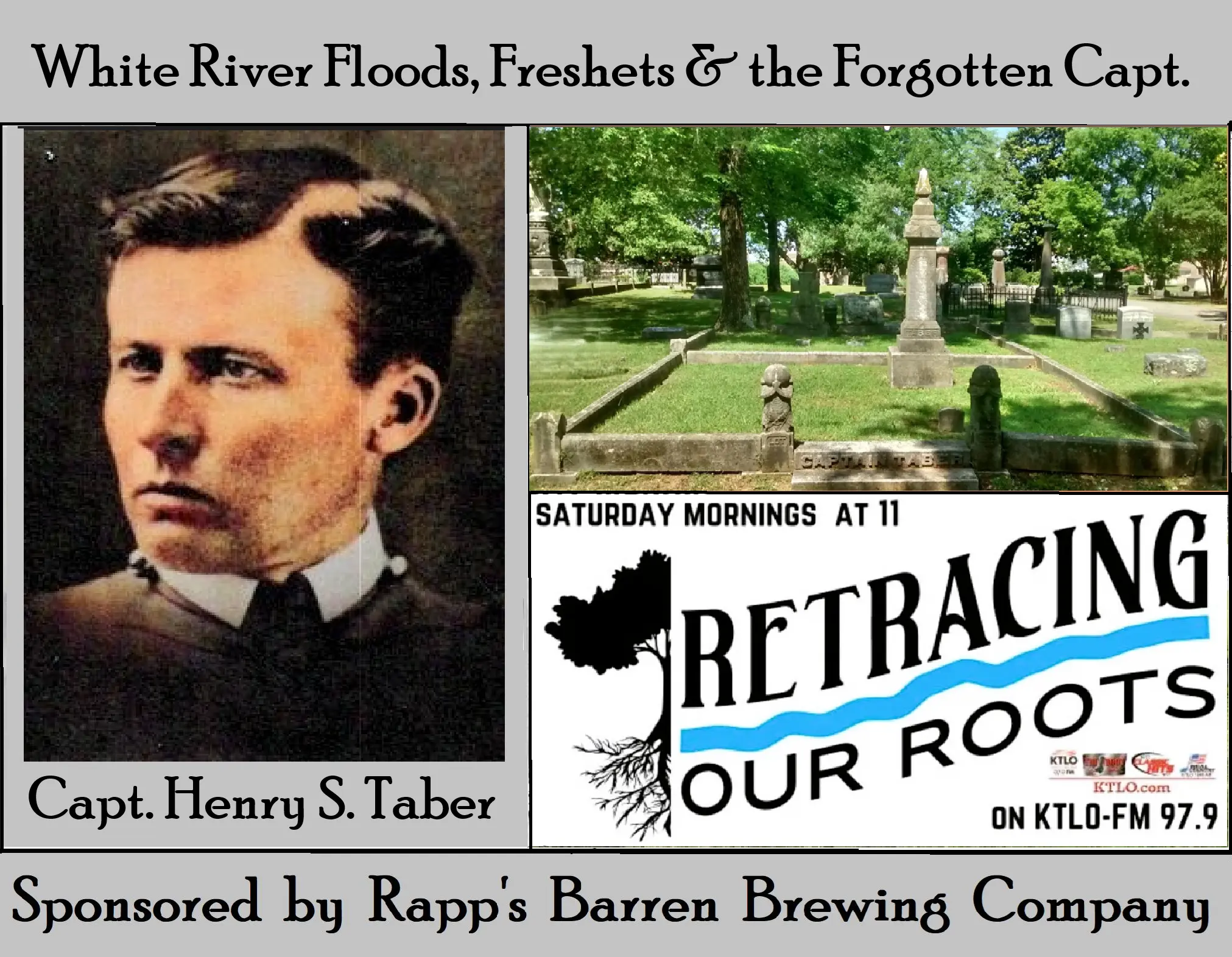

In the decades following the devastating freshets that routinely overwhelmed communities along the White River, a determined figure emerged to help tame the river’s power and harness its potential. Captain Henry Sheldon Taber, a graduate of West Point and a career officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, would become a central figure in shaping the White River’s navigability and economic future during the late 19th century.

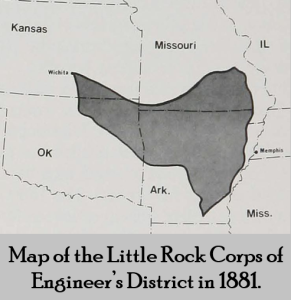

Taber entered West Point in 1869 and graduated second in his class, having excelled in engineering, field fortification, river hydrology, and surveying. His military and technical training would serve him well in his leadership of the Corps’ Little Rock District, where he was tasked with improving river navigation in a region struggling to grow its commerce and infrastructure. While the rise of railroads threatened to diminish river transport, Taber and the Corps shifted focus from the Arkansas River to the White River, recognizing its untapped potential for navigation and trade.

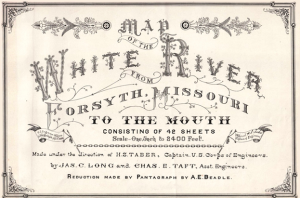

One of Taber’s most remarkable contributions was his comprehensive survey and mapping of the White River from Forsyth, Missouri, to its confluence with the Mississippi. Completed in 1888, his forty-two-plate atlas charted 505 miles of river with impressive detail, including soundings, shoals, ferry crossings, sawmills, and steamboat landings. This map became a critical tool for planning improvements and reflected Taber’s belief that the White River held commercial promise equal to, if not greater than, that of the Tennessee River.

However, not all shared Taber’s vision. Disputes arose between upstream and downstream communities over funding and attention. Editors like W. R. Jones of the Mountain Echo criticized Taber harshly, even calling for his removal. Despite these attacks, Taber maintained his integrity and defended his work through detailed reports that included letters from local citizens testifying to increased trade and improved access due to Corps improvements. Citizens like D. H. N. Dodd of Yellville documented a 100 percent increase in river traffic thanks to Taber’s efforts.

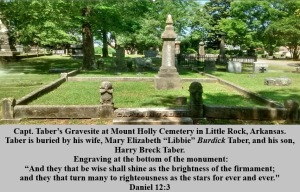

Beyond his engineering achievements, Taber was a man of quiet moral conviction. He and his wife, Mary Elizabeth "Libbie" Taber, opened their home each Sunday to Black children and orphans, teaching them to read the Bible. Taber also served as a leader and treasurer for one of only two Black YMCAs in the South. These actions, especially in the context of post-Reconstruction Arkansas, drew criticism and false accusations, yet the Tabers never backed down from their principles.

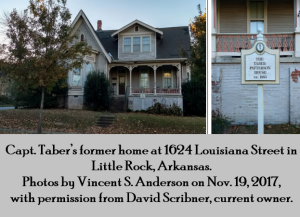

After nine and a half years leading the Little Rock District, Taber took a leave of absence in 1894 due to declining health. He died in San Antonio later that year. He is buried at Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock, alongside his wife and son. His former home still stands on 1624 Louisiana Street, a lasting witness to a man whose vision, humility, and courage helped shape the course of Arkansas’ rivers and the communities that grew along its banks.

A heartfelt thanks to our friends at Rapp's Barren Brewing Company. Their steady support helps Retracing Our Roots keep these Ozark stories alive and resonating through the hills. Partnerships like theirs preserve the real history you won’t find in textbooks. With their passion and hometown pride, we can revive these powerful tales and pass them on to future generations.

Next time you are in downtown Mountain Home, be sure to visit Rapp’s and give a warm shout-out to Russell Tucker and his outstanding team. They are true supporters of heritage and champions of our local past.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

Retracing Our Roots