Welcome to Retracing Our History on a special, historical journey down the White River with Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson. Over the next couple of weeks, we’ll drift back nearly two centuries to revisit the people, places, and events that shaped life along this Ozark waterway.

Before the first white settlers arrived, the White River was already a natural highway through the Ozarks. Native Americans traveled its winding current in dugout canoes. These were simple, sturdy vessels carved and burned out from single tree trunks. These canoes remained common well into the early 1800s. In 1819, the Ozark explorer, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, borrowed a canoe to navigate the western portion of his journey, down the White River, through the Ozarks down to Liberty, Arkansas, present-day Norfork.

At that time, the White Valley region was home to many Native American tribes. The Cherokee, Osage, Shawnee, Delaware, Kickapoo, Piankashaw, and Peoria all had a presence here. The river bound their worlds together, much as it connected the settlers who would soon follow.

The early 1820s brought a period of deep tension between some of these nations. The Cherokee and Osage tribes were at war, and the landscape along the White River became a crossroads of both conflict and survival. On December 28, 1823, acting Arkansas Territory Governor, Robert Crittenden, sent a letter to Washington City reporting that as many as 10,000 Native Americans from various tribes had gathered at the confluence of the Big North Fork and the White River. For the white immigrants who had only recently begun settling the area, fear hung thick in the air.

But by the spring of 1824, nature had written its own chapter. One of the greatest floods of the 19th century swept through the region, known later as the Flood of 1824. The White River rose more than fifteen to twenty feet above flood stage, scouring the bottomlands and reshaping valleys all along its course. When the waters finally receded, many of the tensions that had gripped the area also began to fade. The flood temporally displayed the awe and power of the river itself.

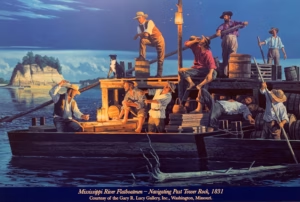

As the years passed, other types of boats began to work the White River. Flatboats were among the earliest. They were built broad, boxy vessels up to sixty feet long and twenty feet wide, with low sides about three feet high. Think of them as floating corrals: livestock crowded one end while a small hut or cabin stood on the other. Inside, a dirt pile served as a hearth for light, warmth, and cooking as the crew carried goods like whiskey, salt, furs, and pelts up and downriver. You can almost imagine the smell the mix of livestock, smoke, and river air drifting through the Ozark hills; think of Noah’s ark.

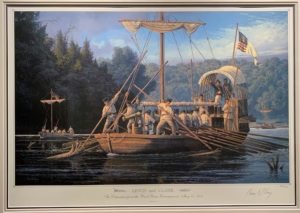

Next came the keelboats, narrow and graceful in comparison to flat boats, measured about seven to ten feet wide and up to sixty feet long. They were powered by long oars with a team of men rowing. Also, poles, or spars, were used which boatmen thrust into the riverbed to push forward, walking along the boat’s side as they maneuvered it up and down the current. If enough speed could be gained before hitting a shoal or gravel bar, the boatmen employed a technique called grass-hoppering, using the spars to “jump” the boat over shallow areas.

Sometimes, keelboats were aided by sails, if the wind happened to cooperate. These were the same style of boats used by Lewis and Clark on their famous expedition.

When wind, river current, or gravel bars presented an obstacle, men would cordell a boat upstream, hauling or towing it by pulling ropes from the shoreline. Later, capstans, used in the early to mid-1800s, were mounted on the bow of the boat, winding the rope as they were turned to make hauling easier.

Around 1837, Jesse Goodman piloted one such keelboat up the White River. Records show that the Flippin family arrived about the same time. Goodman established a trading post where he sold salt, whiskey, sherry, brandy, anything with a bit of spirit in it. His keelboat would later carry bacon, corn, deer pelts, furs, and bear oil down to southern Arkansas and beyond, all the way to New Orleans.

In those early days, the White River was wilder than we can easily picture today. Towering trees met overhead to form a leafy tunnel above the water. Sand and gravel bars broke the current, and hidden perils lurked below. Sawyers, half-submerged logs that bobbed and twisted with the current, and snags or deadheads, solid timbers lying just beneath the surface, were ready to rip through an unsuspecting hull and sink a boat.

By the 1820s, a new era dawned. Steamboats began arriving in Arkansas, and when the first, the Eagle, steamed up the Arkansas River to Little Rock in 1822, excitement rippled through the White River Valley. The White was an easier river to navigate, and many dreamed of seeing steamboats gliding up its winding course.

Federal surveyors and engineers soon followed. Snagboats were sent to clear the dangerous obstructions. Over time, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built wing dams, cut channels, and reshaped the river’s flow to make navigation safer. Stroke by stroke, snag by snag, and season after season, the wild river that once echoed with paddle strokes and bird calls slowly transformed into a commercial thoroughfare.

As the U.S. Corps of Engineers began clearing portions of the river, vast amounts of dynamite were used to crumble boulders and remove large gravel bars so the current could flow freely.

Boys as young as twelve to sixteen were hired by the Corps to be hoisted up on large booms and swung out over the river to cut a path through the canopy so the stacks of steamboats would not be ripped off. Tragic deaths and severe injuries occurred when boys fell and struck boulders or the decks of the boats. Some fell into the swift current and were never seen again. A small compensation was generally paid to the families for the loss of their son.

The banks of the White River were woven with rivercane brakes and lined with tall sycamore, walnut, oak, and hickory, creating a vast canopy over the channel and along the banks. These trees were also harvested for firewood to feed the boilers of the new steamboats plying up the river. Pine knots, loaded with rosin and sap, were a choice commodity; they burned hot, like adding a boost of octane to a steamboat’s boiler.

The heavy cutting of timber along the river led to erosion, and the banks began collapsing into the current. The Corps hired men to weave large mats of willow and rivercane, sometimes up to a hundred yards long. These mats were laid over the eroding bank and held down with boulders. This, however, changed the river’s habitat for certain fish species. The rocks heated in summer, and traditional spawning beds for fish and freshwater mussels were depleted.

Trade on the White River during this period became highly seasonal due to recurring summer droughts. Flatboats, keelboats, and steamboats were often held hostage on sand and gravel bars until the winter or spring floods lifted the stranded vessels.

Trade on the White River during this time became highly seasonal due to recurring summer droughts. Flatboats, keelboats, and steamboats were often held hostage on sand and gravel bars until the winter or spring floods lifted the stranded vessels.

During the summer and fall months, many men went into the forest to cut large logs and build rafts to be lashed together in winter. When the White River swelled with fresh, surging water, young men would ride atop these makeshift rafts down the White, into the Mississippi, and all the way to New Orleans to sell their timber.

With fresh money in hand, many returned home on steamboats carrying supplies for their families. But not all made it out of that Delta city with their fortunes intact. Alcohol and vice had a way of stripping a man of his earnings. Even our 16th president, Abraham Lincoln, had an adventure like this from Illinois to New Orleans. But that’s another story.

As the years progressed, steamboats advanced not only as far as Jacksonport, Arkansas, but also began making landings and postal drops at small towns and settlements along the White River. Calico Rock, Norfork, Buffalo City, Talbert’s Ferry, Trimble’s Landing, and Dubuque became familiar stops on the route. The ultimate goal for many steamboat captains was to reach Forsyth, Missouri, so that trade could be carried farther up the James River to Springfield. Much of the Ozarks became reliant on the White River.

Jesse Mooney holds the distinction of being Marion County, Arkansas', first steamboat owner, taking possession of the Thomas P. Ray in early part of 1856. This small steamboat operated along the Upper White River. Unfortunately, its financial footing was chaotic and fragile. Trouble arose when Jacksonport merchants Pool and Watson filed a claim for supplies and funds previously provided to the vessel’s former owner, Captain Oaty P. Dowell, prompting the sheriff to seize the boat.

Mooney, together with Captain Francis A. Maffitt, successfully appealed the case in Circuit Court, which overturned the initial judgment. Pool and Watson later pursued their appeal to the Arkansas Supreme Court.

Under its new proprietors, the Thomas P. Ray went back into service on the Upper White River, with Captain Maffitt at the helm. As storms brew in the White River valley, disaster struck in early summer when a storm at Batesville tore the vessel from its moorings, sinking it in eight feet of water and inflicting heavy damage to both the boat and its cargo. The steamer was soon raised and repaired, but ownership changed once more. On November 22, 1856, Captain Maffitt sold the Thomas P. Ray to George Pearson of Oakland in Marion County for $2,500. According to historian Donald Harrington, the transfer tike of the steamboat was not officially recorded until December 25, 1857.

Pearson thus became the vessel’s final owner, and the Thomas P. Ray started working the White River once more.

In the beginning of May, 1856, a violent storm hit the White River Valley in Batesville, Arkansas, and the Thomas P. Ray suffered the consequences. An article from the Times-Picayune in New Orleans, Louisiana, on May 10, 1856, stated:

"...a heavy storm of wind and rain prevailed on Wednesday evening last, at Napoleon [Arkansas], which extended up White River to near Batesville, doing a good deal of damage. The steamer T. P. Ray was sunk in the same storm in White River, near Batesville. We have not heard from the effects of the storm up the Arkansas river, but fear, from its destructive violence elsewhere, that we shall yet hear of."

About nine months later, a newspaper report on February 27, 1857, observed: “The Thomas P. Ray unexpectedly made her appearance yesterday for the Upper White. We admire her pluck…”

The hardy little steamboat remained a familiar sight on the upper river, making frequent trips from Mooney's Landing to Batesville. As late as March 1858, it was documented loading cargo in Batesville, including salt, whiskey, and other goods bound for Marion County. During that boating season alone, the Thomas P. Ray carried more than 3,000 sacks of salt, numerous barrels of whiskey, and tons of other merchandise up the White River.

McBee Steamboat Landing stood on the White River upstream from Cotter, Arkansas. The abandoned steamboat landing lies just a quarter-mile south of the Highway 62 Bridge, between on the Marion County riverbank, and only 0.8 miles above the railroad bridge. It was also known as the Yellville Steamboat Landing. Many important steamboats, keelboats, and flatboats loaded and delivered freight here.

By October 1861, the “elegant and swift passenger steamer” Dr. Buffington had been renamed Eliza G. and placed into the Upper White River trade. The Dr. Buffington, a side-wheel paddleboat, was built in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1857 for A. J. Buffington of New Orleans. Measuring 180 feet long and 33 feet wide, the vessel could operate in as little as 25 inches of water. Described as a “beautiful, new, and splendid fast passenger steamer” designed for the Ouachita River trade, it first reached New Orleans in January 1858.

By 1860, the Dr. Buffington was renamed Eliza G., it was commanded by J. H. Quisenbury (or Quisenberry) of Batesville, Arkansas. By February 1862, its route expanded to the Little Red River, offering service to “Pocahontas, Jacksonport, Des Arc, and all landings” along these three waterways.

The Eliza G. later served as a Confederate transport and was present at St. Charles in June when a Union fleet carrying supplies for Major General Samuel R. Curtis’s Army of the Southwest approached. Confederate engineer Captain A. M. Williams recorded that, under orders from Major General Thomas C. Hindman, the Eliza G. and two other steamboats to be scuttled on June 17, 18621, in the White River channel to blockade the Union flotilla. The Eliza G. still rests beneath the waters along the St. Charles riverbank.

Still, the story of the White River remains one of persistence of people and water shaping each other across centuries, carrying echoes of every canoe, keelboat, and steamboat that ever passed between its wooded banks.

𝐓𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐤𝐬, 𝐑𝐚𝐩𝐩’𝐬!

A special thank you to Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company for their sponsorship of 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨. Their continued partnership helps us share the real stories of the Ozarks. These kinds of stories are not always found in textbooks, but we share them heart to heart. It’s thanks to local supporters like Rapp’s that these voices from the past still echo through our hills.

We invite you to stop by Rapp’s in downtown Mountain Home and thank Russell Tucker and the whole crew. Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company is helping us pour heart into our local history.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨