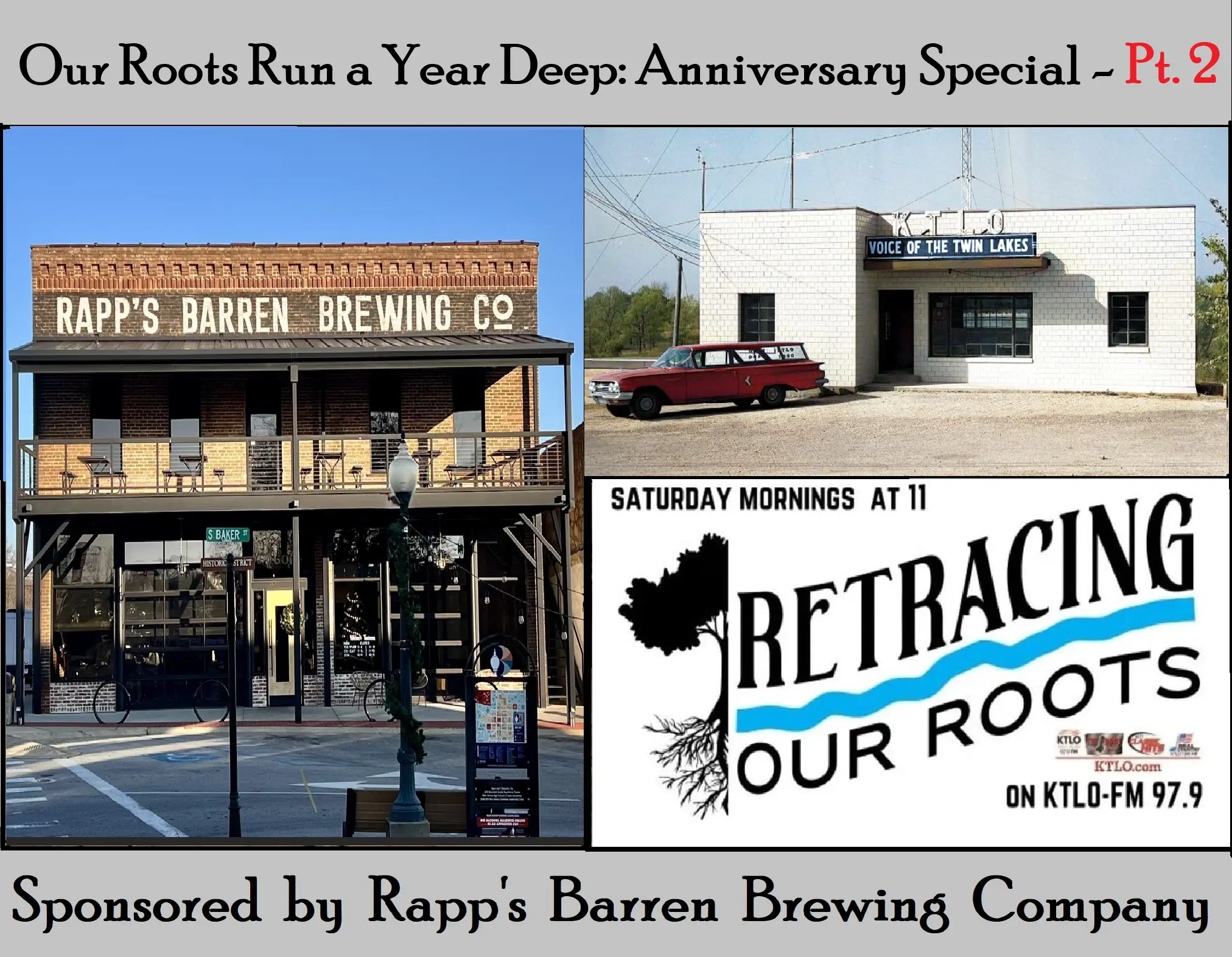

Welcome to a very special edition of Retracing Our Roots with Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson. Today, we are celebrating a milestone together. One year ago, we set out on this journey to uncover the stories, the people, and the heritage that make the Ozarks what they are.

Over the past twelve months, we have walked the trails of history, dug into forgotten corners, listened to voices long gone, and honored the memories that still shape our lives today.

When we began last year, our theme was water, specifically, the White River Valley. From there, we explored what makes the Ozarks unique, focusing on the Twin Lakes region.

This week in our anniversary series, we turn to “Retracing Our Roots: Clash of Nations in the Ozarks.”

By the early 1800s, hundreds of families had settled along the White and Arkansas Rivers, stretching toward Batesville and what became Marion and Baxter Counties. The land reminded them of their Appalachian homelands with fertile bottomland for corn, abundant game in the hills, and room for cattle and hogs.

By 1812, more than a thousand Cherokee had moved into the Arkansas Valley, many traveling up the White River to hunt and trade. The Quapaw, native to Arkansas, welcomed some of these Cherokee families, while Delaware villages appeared along tributaries like the Strawberry and Black Rivers. The Shawnee, some settling near present-day Yellville, once known as Shawneetown, became important cultural middlemen, connecting Cherokee, Osage, and white settlers. Their territory stretched into Missouri’s Ozark and Douglas Counties and into the White River Valley. Yet year after year, hunting and farming grounds were lost through treaties signed far from their homeland.

Their stories connect with those told in A Stranger and a Sojourner: Peter Caulder, Free Black Frontiersman in Antebellum Arkansas by Dr. Billy D. Higgins. This work highlights men like Caulder and David Hall, who carved out lives of resilience and freedom in a turbulent land.

The echoes of these displacements still linger. Place names, trading paths, and unmarked burial grounds whisper of those who lived here before counties were drawn and borders were settled. Walking along the White River or across the Bootheel, we move through a layered landscape of treaties, migrations, and memories where nations like the Osage and Cherokee lost their homes, and figures like John Hardeman Walker redrew the land.

We also looked at the Jacob Wolf House, perched on a hillside at the meeting of the White and North Fork Rivers. Today, we know Liberty as the town of Norfork, Arkansas. Built in 1829, the Jacob Wolf House is the oldest, two-story, dogtrot, public building not only in Arkansas but west of the Mississippi River. Its preservation reminds us that Ozark history is not just stories but living landmarks.

Some stories are more tragic. On March 18, 1956, Samuel David Napier, age twelve, and Philip Wayne “Shorty” Cantrell, age thirteen, set out to explore Bergman Cave in Calico Rock. By nightfall, the boys had not returned, and search parties scoured the cave and the banks of the White River. Almost two years later, on March 2, 1958, bones and scraps of clothing were found in a smaller nearby cave known as Needles Cave. Families confirmed the remains, and the Arkansas State Police determined no foul play was involved. Today, the boys rest together in one grave plot at Spring Creek Cemetery near Calico Rock.

In the late 19th century, the White River became the stage for another chapter, “Floods, Freshets, and the Forgotten Captain.”

Captain Henry Sheldon Taber, a West Point graduate and officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, rose to the challenge of taming the White River’s unpredictable floods. Assigned to the Corps’ Little Rock District, Taber envisioned the river as a vital artery of commerce and trade.

In 1888, he completed a sweeping forty-two-plate atlas of the White River, charting 505 miles from Forsyth, Missouri, to the Mississippi. His maps detailed soundings, shoals, ferry crossings, mills, and steamboat landings. They were more than technical records. They testified to his belief that the White River held commercial promise.

Not all of our stories came from the distant past. From early 1984 through the autumn of that year, the Marion County-based militia known as the Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord, or CSA, made headlines across the Ozarks. By the spring of 1985, the group captured both national and international attention.

Occupying a 224-acre compound in the northeastern corner of Marion County near Oakland, Arkansas, the CSA began as a small Baptist congregation known locally as the Zarephath-Horeb Community Church. For years it lived in relative obscurity until April of 1985, when more than 300 officers surrounded the compound in a raid that ended its activities. Today, that acreage has been divided and the former base is private property.

The land itself carries memory. The prairies and forests are not just scenery but the original estate of this region, shaped by fire, biodiversity, and the stewardship of Native peoples who lived with the land.

These are just some of the high points from our first year. It has been a journey of discovery, honoring the people and places that make the Ozarks timeless.

A big thank you to our friends at Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company. Their ongoing support is what helps Retracing Our Roots echo through the hills with the true stories of the Ozarks, stories you will not find in the average history book. It is partnerships like theirs that keep our heritage alive, one story at a time.

Next time you are in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and his incredible team. They are helping preserve local history with heart and hometown pride.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

Retracing Our Roots.