Welcome to Retracing Our Roots as Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson begin documenting the struggles of the Civil War along the White River Valley. This journey is far too vast to be covered in a single episode, but we will walk you through the heartbreak and hardships experienced during the War Between the States.

As the Civil War swept through the Ozarks, it's hard to view any community or family as true "winners," given the widespread death and destruction that ravaged the region. Alongside the bitter weeping and mourning, we will also discover moments of humor—because even in war, the human spirit finds ways to laugh through the tears.

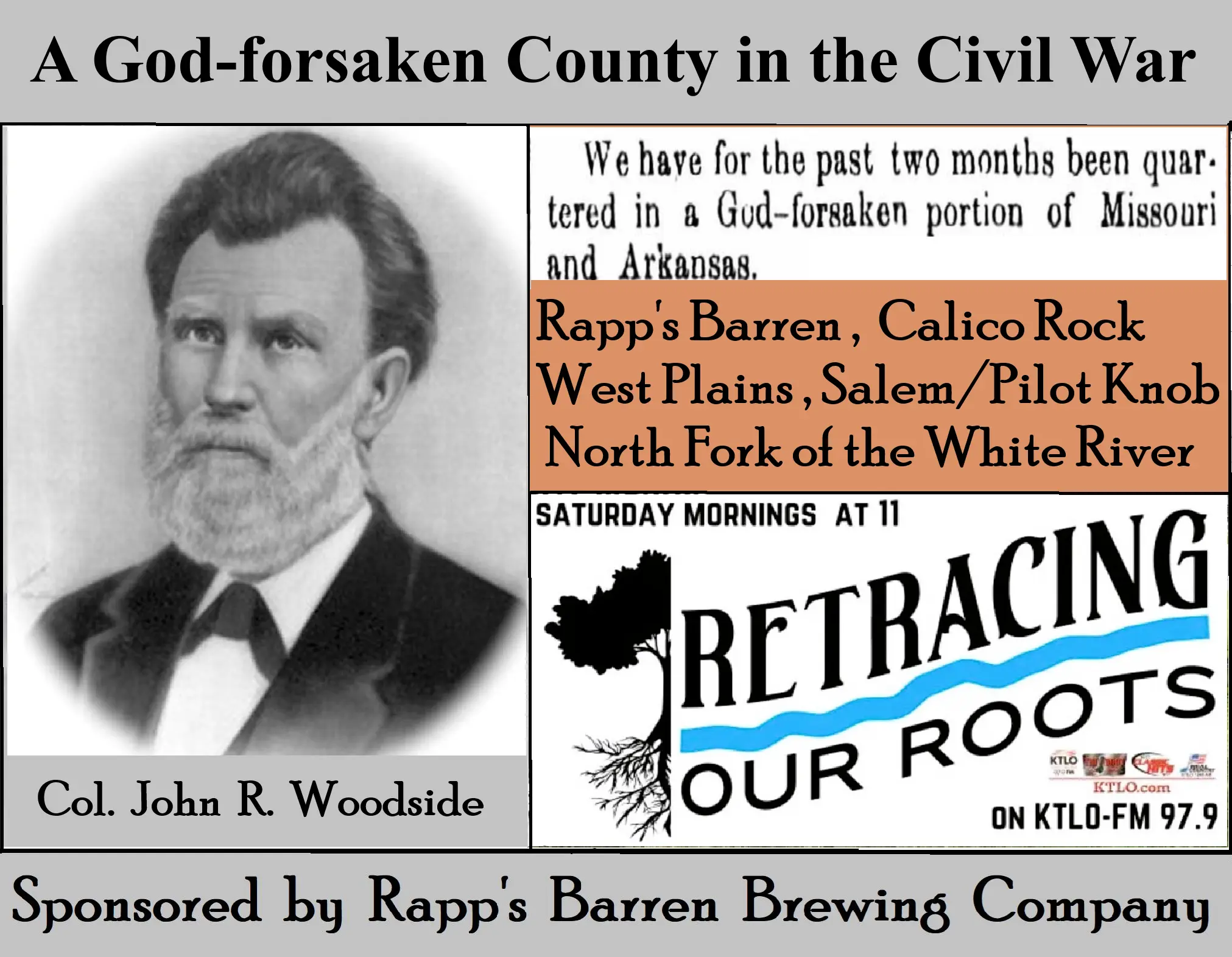

As we delve into the local events of the Civil War in our area, we come across a letter written by John Quincy Adams Floyd, which was printed in several newspapers across Illinois. In his correspondence, we begin to see how the Ozarks were perceived by the 1st Illinois Cavalry—as a “God-forsaken portion of Missouri and Arkansas.”

Eventually, Floyd and about 500 men of the 1st Illinois Cavalry were stationed in Houston, Missouri, under the command of Colonel Thomas Alexander Marshall, Jr., who also served as the Lieutenant Governor of Illinois.

It was Floyd’s letter that first caught my attention. In its details, he describes a venture he led into Salem and Mountain Home, Arkansas. These accounts are corroborated by the memoir of John Greer Deatherage, a former Union soldier of the 9th Regiment Provisional Missouri Militia, Company K. In his memoir, Deatherage, a pioneer of Gassville, Arkansas, recounts that he and other Union sympathizers from his neighborhood near Talbert’s Ferry on the White River traveled to Salem to assist Colonel Marshall and the 1st Illinois Cavalry. John G. Deatherage is buried at Three Brothers Cemetery in northern Baxter County, Arkansas.

On a personal note, I believe this is one of the earliest references to Mountain Home resident Orrin L. Dodd in the context of the Civil War. This predates the Skirmish and Raid at Mountain Home by just over four months, which occurred in October 1862.

The following is John Q. A. Floyd’s letter in its entirety so that his voice may be heard once more, and so that some of the wartime details involving a portion of the Missouri-Arkansas Ozarks might come to light.

Letter from the First Cavalry.

Houston, Texas Co. [MO.], June 14, 1862.

Editors of the Illinois State Journal:

“Sirs: Have the kindness to insert into your paper, which by the way is patronized and perused by many, if not all the parents and friends of the members of the First Illinois Cavalry. The short statement I desire too, and feel is my duty to make, in regard to the present condition of the First Cavalry, as I deem it but justice to the officers and men of the same.

We have for the past two months been quartered in a God-forsaken portion of Missouri and Arkansas. Two companies are at this place; three companies at West Plains, Mo.; and three companies were at Salem, Ark. Salem, the seat of Fulton County, is located at the foot of Pilot Knob. The clear water of the South Fork of the Spring Rive

A band of rebels, led by one Coleman [Col. W. O. Coleman], has committed some depredations in the vicinity of Houston [Missouri], and between here and Rolla, Mo. He also took three men prisoners of company B, relieved them of arms, horses and equipment, and set the men free again.

We had several scouts from Salem, Arkansas, Company F, Capt. Burnap went out on the 20th of May in pursuit of a band of rebels; came in sight of them at a point called Calico Rock, on White River; exchanged a few shots across the river; not know what damage we done them, for after they received one or two light volleys, they played their old game—ran for life. They had the boat on their side of the river, so we could pursue them no further. We had one man slightly wounded in the thigh, (Emery Debble, from near Peoria.)

Again, on the fifth of June, Col. Marshall took parts of three companies under his command at Salem, 150 men strong, and started southwest towards Yellville, where it was reported that the rebels ranged in great abundance. The first day’s march, thirty miles, was marked by no interesting or thrilling event. We camped on a creek near the North Fork of White river, and the next day we crossed the North Fork of the White River, and continued southwest. Company F, was detailed to proceed in advance for four miles, to a Mr. Dodd’s [Orrin L Dodd].

On that march we captured a small sandy complexioned Southern gentleman, who, upon search proved to be Col. Woodside [Col. John Rowlett Woodside] of Missouri, a prominent secesh [Confederate].

We soon after that heard of a small band of rebels, headed by Capt. Grant, being in that vicinity. When we approached near Mr. Dodd’s we discovered two mounted rebels; J. H. Sprigs [ J. W. Spring] and myself led out after them, had a pretty race of some three hundred yards, when we succeed in capturing one man, horse and equipment.

About the same time, I saw a butternut in the bush near by with a good shotgun. I halted him, but he ran and I fired. I do not know wither [whether] he was hit or not, but I do know that he did drop a good shot gun, and I still have it in possession.

The other two companies came up soon after. I then took nine men and went out on a scout, captured four persons in about one hour and did not get a shot; but I am sorry to say, the rule here adopted with prisoners, if not caught in arms or aiding rebels, they are released by taking the oath of allegiance. It goes hard with Illinoisans to protect the property of those we believe are at heart traitors and rebels. Thousands take the oath for no other reason than to save their property, and I know of instances where they went straight home and took up arms against us.

When we were between North Fork and White river, we within a few miles of three rebel camps. Just about dusk on Friday evening, June 6, a messenger arrived with orders for our seven companies to report immediately at this post, Houston;

I submit this

to you and your readers, hoping it will prove of some interest to the people of Sangamon. Capt. Burnap is in good health, but, like all the rest, he shows he has been out in the weather.

I am yours, most respectfully,

Lieut. John

Q. A. Floyd”

As the war progresses into the autumn of 1862 in the White River Valley, movement begins with the local men from Northern Arkansas enlisted in the 27th Arkansas Infantry station in Pocahontas, Arkansas. As orders go out to strike camp and leaves, the 27th receives ordered to reconstitute in Yellville, Arkansas, within a 10-day period. According to a soldier and historian within the 27th, Silas C. Turnbo, those wanting to leave early devise a plan to get leave early by faking to be sick. Wads of chewing tobacco were quickly swallowed, and men “fell ill’ with severe stomach distress.

On Saturday morning, October the 10th, furloughs for sickness were distributed by the camp surgeon. As soldiers left camp, miraculous healings began manifesting among the seemingly “unfit for duty.” Eyes were set westward toward their westward destination of Yellville. Some “sick” men would, astonishingly, make the 130-mile trek in less than seven days. This gave them the luxury of visiting home and the chance to see family or friends.

Five days into the journey, soldiers were constantly on the lookout for any fresh spring of water. Some men would stray up to a half-mile off the Old Military Road in search of a water source. According to reports, evening rations of water often contained dead lizards and toads settled in the bottom dregs of their tin cups. Some were so desperate for a drop that they knelt in the road to lap up the last diluted remnants from mud puddles. Others placed small, smooth stones in their mouths, rolling them over their tongues in hopes of extracting any moisture.

Among those reported as sick was a man of reputation, Maj. John Woodward “J. W.” Methvin of the 27th Arkansas Infantry, Company A. Without question, he was suffering from a severe case of pneumonia. He was so ill that it was determined he couldn’t make the journey on horseback. Another officer offered to transport him in a hack (buggy) to Yellville.

The 45-year-old Confederate major, originally from Madison County, Alabama, was looking forward to seeing his wife, Corasandra (Nowlin) Methvin, who lived near the small village of Dubuque, Arkansas, on the White River. John Woodward and Corasandra had been married for nine years. It had also been nine months since John last seen their four children: Alonzo, Josephine, Hannah, and James.

[Dubuque was among the earliest settlements established in what is now Boone County, Arkansas. Dubuque gained some prominence as a river crossing but was nearly wiped out during the Civil War and never fully rebounded. Today, the original town site rests beneath the waters of Bull Shoals Lake.]

Before the war, Methvin had the honor of serving as Marion County Circuit Clerk from 1858 until his enlistment in the Confederacy. While many Marion County men joined the 14th Arkansas Infantry in the first year of the war, Methvin briefly served in the Arkansas State Troops, 5th Regiment, Company E. By June 30, 1862, he had returned to Marion County to help form Company A of the 27th Arkansas Infantry; he was elected 1st Lieutenant.

Maj. Methvin was a Southern gentleman of known integrity, defending his men from officers like Col. Shaler, who often attempted to take advantage of subordinates. Therefore, in his time of need and sickness, hospitality was extended to him in return. Methvin completed the final leg of his journey, arriving in Mountain Home, located on Rapp’s or Talbot’s Barrens (Prairie), in just six days.

Little did Methvin know of the Union plans already in motion, or the disheartening surprise that would await him at Col. Casey’s house in Mountain Home, Arkansas.

[Classic cliff-hanger!]

A warm and sincere thank you to Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company, our steadfast supporters of 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨. This is what real, hometown storytelling looks like: where shared memories tie a community tighter than any ordinance ever could. Without the heart, heritage, and help of folks like Rapp’s, we couldn’t do what we do of reviving the past and passing it along, one story at a time.

Next time you're in Mountain Home, swing by Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company and thank Russell Tucker and his top-notch crew for championing local history that still matters.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn. — 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨

Got a piece of history or local legend you'd like to hear more about?

We're all ears!

So, drop us a line, and we’ll dig it up.