Welcome to 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨 as Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson delve into the Civil War conflict in Mountain Home area. But first, we have listeners want more information of two gentlemen in our previous episode.

Lt. John Quincy Adams Floyd

Born in 1827 in Middleton, Ohio, and named after a sitting president, John Quincy Adams Floyd came of age with the young American republic. He later settled in Springfield, Illinois, where he became a well-respected grocer and community figure. But Floyd was more than a merchant—he was a patriot. During the Civil War, he served honorably as a First Lieutenant in Company F of the First Illinois Cavalry Volunteers.

After the war, Floyd returned to civilian life, continuing to serve his community with quiet dignity. On July 13, 1895, at age 68, he passed away at his home. He left behind a widow and four children, and was laid to rest in Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery, just steps away from the tomb of Abraham Lincoln.

Col. John Rowlett Woodside

Born in 1814 at Rowlett’s Landing, Kentucky, John R. Woodside left a lasting mark on Missouri’s legal, educational, and wartime history. From schoolteacher to lawyer, he eventually served in the Missouri Legislature and as Circuit Judge for 16 years. A staunch Democrat and Civil War Confederate colonel, Woodside fought at Wilson’s Creek and was captured three times—including once while recruiting in Mountain Home, Arkansas.

After surviving over a year in Gratiot Street Prison, he returned to civilian life and helped shape regional identity, most notably by naming the town of West Plains. Woodside died in Thomasville in 1887 and is buried in the cemetery that bears his name, a lasting monument to a complex figure who helped define Missouri’s Ozark frontier.

A Plundering Expedition

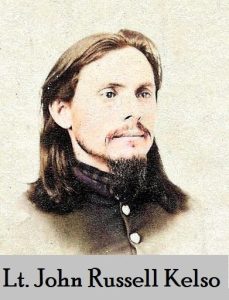

Today, we retrace a troubling path through the fall of 1862, where one officer’s conscience stood against the tide of corruption, cruelty, and cowardice within his own ranks. This story emerges from the first-hand account of Lieutenant John R. Kelso, a teacher-turned-soldier in the 14th Missouri State Militia Cavalry. What began as a supposed military campaign into Arkansas quickly unraveled into something far more disgraceful.

In September of that year, Union forces constructed a fortified blockhouse atop Sugar Loaf Hill, overlooking the town of Ozark. They used double log walls and a six-foot-high enclosure to protect against rebel guerrillas. Within this perimeter, Kelso reunited with his family from Illinois. His wife, more affectionate than he expected, lifted his spirits, and his pride in his three children swelled quietly in the background of the war.

By October of 1862, the focus shifted. Major John Wilber organized a raid into northern Arkansas, supposedly to strike at Confederate forces in Yellville. But there was a problem. This mission lacked official sanction, and the White River was fully flooded. Officers known for their honor were intentionally excluded. Kelso suspected the truth: this was not a mission of strategy, but a mission of plunder.

Kelso did not mince words. He observed, “Had he [Maj. Wilber] meant warfare, he would have wanted officers who were fighters and not those only who were thieves.”

Tensions rose immediately. During the march to Tolbot’s or Rapp’s Barren, Captain Flagg continually pushed to the front of the column, seeking first pick of any loot. When Kelso confronted him, he declared that he respected his two horses more than Flagg, whom he considered a pitiful substitute for an officer.

On October 16, their march took them deep into Rapp’s Barrens. Wilber and Flagg began entering homes uninvited, stripping them of food, valuables, and dignity, while forbidding the rank-and-file soldiers to step out of formation. In one home, they abducted a young mother from her infant child and demanded she offer herself in exchange for her freedom. Only after the pleas of shocked soldiers was she finally released.

Later that evening, they arrived at a fine home occupied by two orphaned sisters, most likely the Goodall family near present day Pizza Hut in Mountain Home. Flagg barged in, claiming every possession as his own—from the milk to the beds. When a hungry soldier attempted to drink some milk, Flagg berated him publicly. That’s when Kelso snapped. Stepping between them, he flung his fist under Flagg’s nose and shouted, “You infernal cowardly thief!” Flagg, shaken, retreated behind Wilber like a frightened boy hiding behind his older brother.

The next day, the 17th, brought no relief. At a large home owned by a dying banker, mos likely at the Dodd home, Flagg tore a gold watch from the man’s daughter as she cried, "It was a gift from my poor sick father." Her pleas, Kelso wrote, were in vain. Meanwhile, Wilber and Flagg each claimed an enslaved woman as a “cook,” though the implication was clear: these women were intended for more than kitchen work.

Wilber’s treachery escalated. After plundering the home of gold and goods, he sent Kelso and his men on a diversionary scouting assignment. The timing was no coincidence. In Kelso’s own words, “He meant to be a murderer, to hush my testimony.”

While Kelso’s party evaded rebel patrols in the woods and creeks of north Arkansas, Wilber’s forces retreated in haste. Rebel troops struck the rearguard under Lieutenant Mooney near present day Tucker Cemetery Road, and though Union, Lt. Mooney bravely broke through with no losses, the entire operation reeked of chaos, betrayal, and self-preservation. At least 10 Confederates were killed and 30 prisoners were taken to Ozark, Missouri.

Upon their return, Kelso’s scouts were met with relief. The enlisted men, furious at Wilber’s conduct, muttered threats. One said plainly, “His life and Flagg’s must atone for Kelso’s, if lost.” Wilber, realizing the tide had turned, welcomed Kelso back with a smile that barely concealed his fear.

In the days that followed, Kelso’s reputation soared. Civilians remembered his decency, while Wilber and Flagg were branded as cowards and criminals. The final confrontation came when Wilber tried to shift the blame to another officer named Burch. Kelso stepped forward, clenched his fist again, and said quietly but firmly, “Just squirm, and I will tear you limb from limb.” Wilber turned pale and trembled.

Kelso, though a fierce Unionist, stood alone in this expedition as a protector of the innocent women, He later wrote, “Never was our flag more thoroughly disgraced.”

And yet, through it all, Kelso’s light did not go out. Kelso would become friends with a notable Baxter County native.

A warm and sincere thank you to Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company, our steadfast supporters of 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨. This is what real, hometown storytelling looks like: where shared memories tie a community tighter than any ordinance ever could. Without the heart, heritage, and help of folks like Rapp’s, we couldn’t do what we do of reviving the past and passing it along, one story at a time.

Next time you're in Mountain Home, swing by Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company and thank Russell Tucker and his top-notch crew for championing local history that still matters.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn. — 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨

Got a piece of history or local legend you'd like to hear more about?

We're all ears!

So, drop us a line, and we’ll dig it up.