Welcome to 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨 as Heather Loftis, Adam Rogers, and Vincent Anderson journey into a much requested topic: True Crime in the Ozarks.

In the volatile years following the Civil War, the Ozarks remained a rugged and often lawless frontier. Although Reconstruction officially ended by the mid-1870s, much of the region remained fractured, with isolated communities, minimal law enforcement, and smoldering resentments from the conflict. In this vacuum of order, some citizens took justice into their own hands, forming clandestine vigilante groups known collectively as the Bald Knobbers.

These groups were not one unified body but a regional phenomenon stretching across southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. They emerged in counties like Christian, Taney, and Ozark in Missouri and Boone, Marion, and Baxter in Arkansas. Sometimes they dissolved after a single act of retribution; other times, they became deeply woven into local society—feared, respected, or outright loathed. The root cause was almost always the same: unchecked crime, corruption, and a breakdown of civil authority.

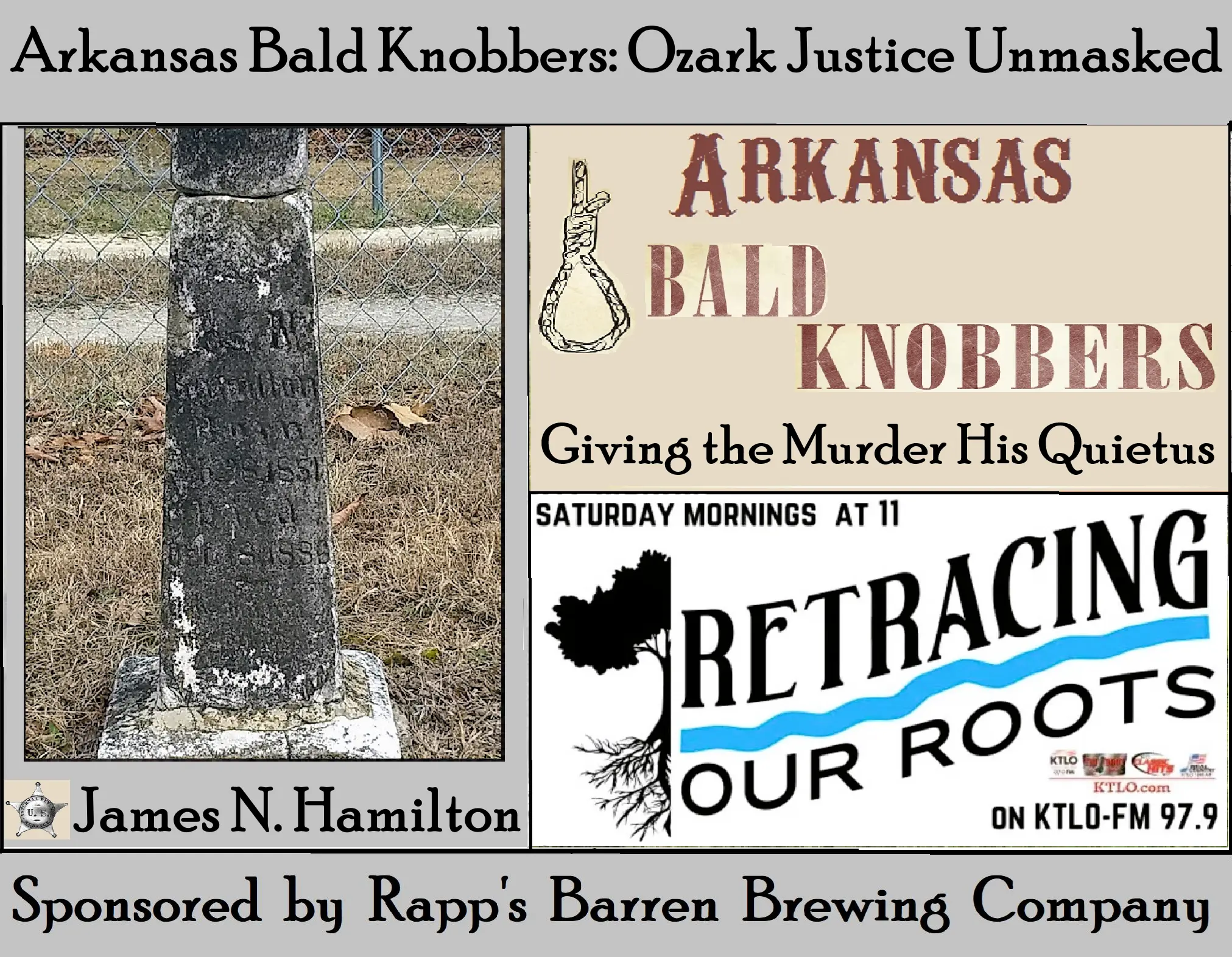

We can be reminded of this history, while visiting Oakland Cemetery in northern Baxter County. Among the aging stones stands a cracked obelisk marking the grave of James N. Hamilton, a former lawman and federal revenue agent. His assassination in 1886 sparked one of the most unsettling chapters in Ozark vigilantism.

Hamilton, originally from Searcy County, Arkansas, had served as sheriff and county clerk before joining the U.S. Treasury Department. As a “revenuer,” he was tasked with rooting out illegal whiskey stills—an occupation as dangerous as it was unpopular. After relocating to Marion County with his wife, Nora, and their young son, Hamilton intended to run for sheriff again. He settled on farmland near Oakland, along Cane Bottom Bluff.

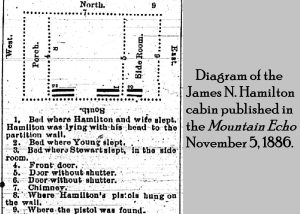

But on the night of October 18, 1886, death came quietly. As Hamilton lay asleep beside his wife and child, a gunman crept into their cabin and fired a shot into his head. His last words—“Oh, Lord!”—rang into the night. He was buried the next day in what was then known as Yocham Cemetery.

Speculation about the motive swirled: Was it political rivalry? A whiskey feud? Or something more personal? Hamilton had recently employed two men—James Page and James Stewart—to help clear his land. Suspicion soon fell on Page, who was arrested and held in the Marion County Jail.

But justice in the 1880s Ozarks rarely followed a straight line. Fearing mob violence, officials tried to move Page for his safety. Too late. A group of armed, hooded men, presumed Bald Knobbers, stormed the jail and took him to the woods to lynch him. In the chaos, Page escaped into the hills. He was later tracked down and captured by a posse led by Hamilton’s father-in-law, Jasper Wayne Hensley, himself a seasoned local official.

Only then did the truth emerge. “James Page” was actually Andrew Jackson Mullican, a fugitive from Clinton, Arkansas. His motive? He confessed to being in love with Nora Hamilton and claimed he killed her husband in a fit of passion.

His confession enraged the region. Though he was moved to Harrison for safekeeping, the people weren’t satisfied. On a stormy night, November 11, 1886, around fifty masked men surrounded the Boone County Jail. They roused Deputy Johnson from his bed, forced the keys from him, and dragged Mullican from his cell. Though the plan was to hang him, the noise alerted nearby townspeople. In a panic, the mob shot him seven times and left his body beneath a tree. The coroner later ruled he’d been killed “by unknown persons.”

This grim episode laid bare both the raw effectiveness and the terrifying cost of vigilante justice. Bald Knobbers didn’t always fight for noble reasons, nor did they always strike the guilty. But in a time and place where courts were weak and sheriffs outgunned; many believed they were the only justice available.

Today, Hamilton’s monument still stands near Highway 5, weathered by time and wind. His story—and the brutal end of his killer—reminds us that frontier justice often came at night, cloaked in mystery, and driven by desperation. It leaves us with a haunting question: When official justice breaks down, how far are people willing to go to enforce their own?

A heartfelt thanks to our friends at Rapp's Barren Brewing Company. Their steady support helps Retracing Our Roots keep these Ozark stories alive and resonating through the hills. Partnerships like theirs preserve the real history you won’t find in textbooks. With their passion and hometown pride, we can revive these powerful tales and pass them on to future generations.

Next time you are in downtown Mountain Home, be sure to visit Rapp’s and give a warm shout-out to Russell Tucker and his outstanding team. They are true supporters of heritage and champions of our local past.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

Retracing Our Roots