𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨

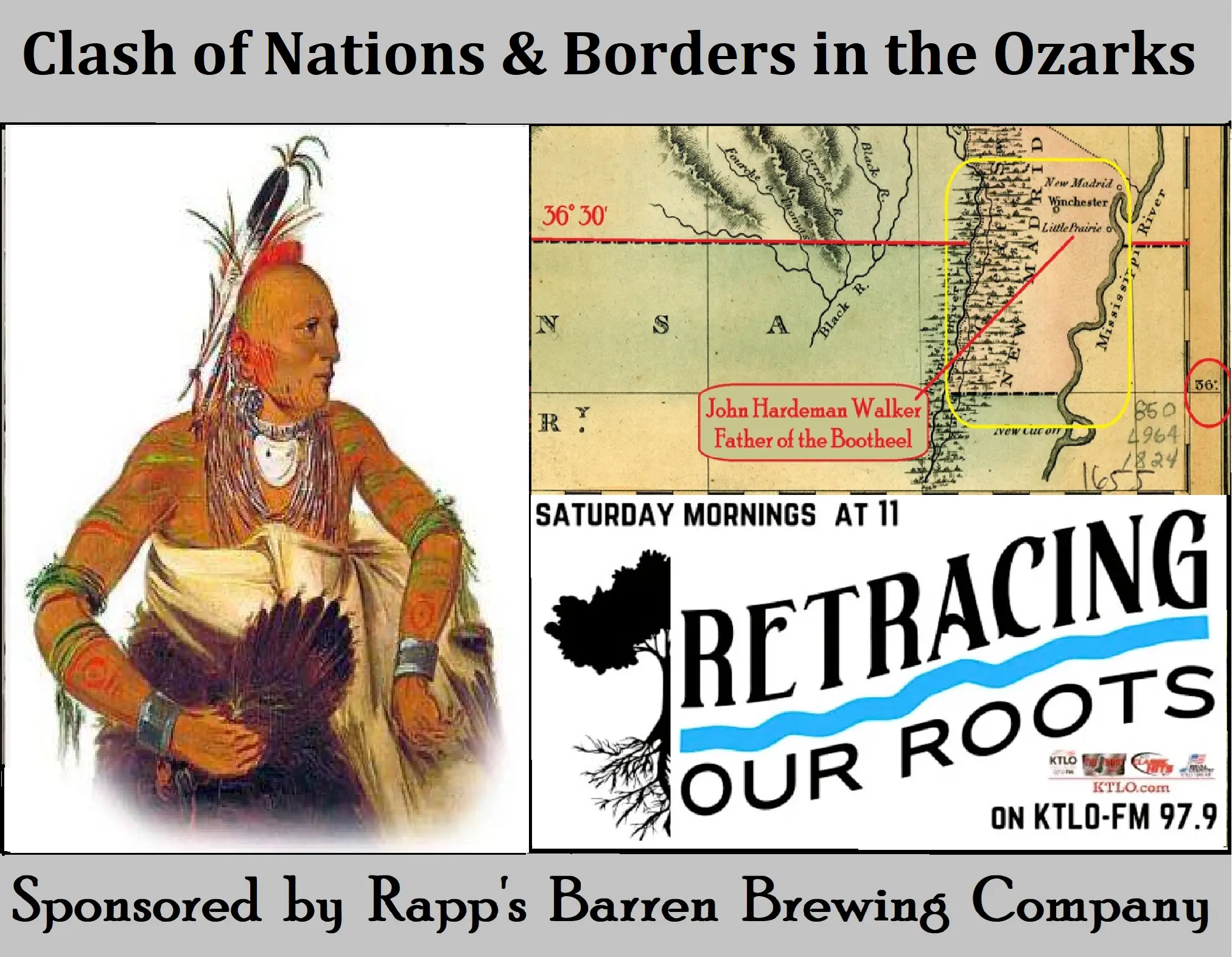

Clash of Nations & Borders in the Ozarks

Welcome to 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨 as Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson travel back over 200 years and step into the violent struggle for dominance between the Cherokee and Osage Nations in the Ozarks. These clashes were not only about land, but about honor, survival, and the right to call the hills and valleys of the White River home.

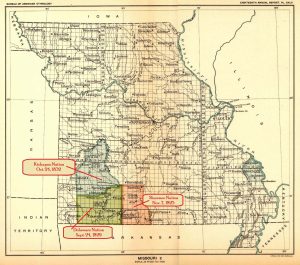

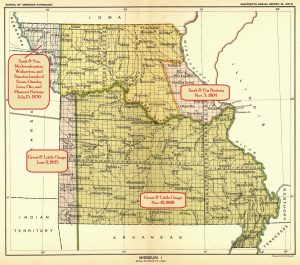

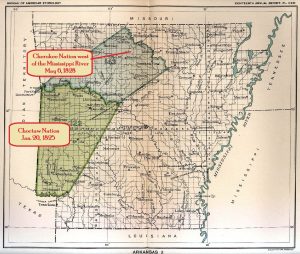

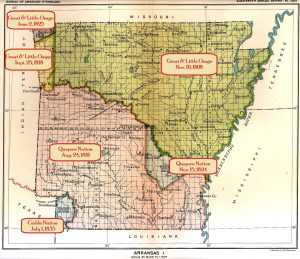

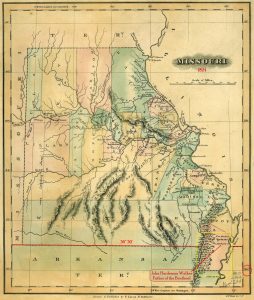

In 1803, the Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States and set into motion a chain of events that would forever reshape the Ozarks. The land deal between Jefferson and Napoleon included what is now Arkansas and Missouri, but for the people already here, the Osage, Quapaw, Cherokee, Delaware, Shawnee, and others, the purchase was not an open door to opportunity but the beginning of a long struggle for survival.

The Osage Nation had long been the undisputed power in the region. From their villages along the Osage River in present-day Missouri, they dominated hunting grounds that stretched across the Ozarks into northern Arkansas and as far west as the plains. Early travelers described Osage hunting parties filling the valleys of the White River and Buffalo River, leaving their mark on nearly every ridge and crossing.

In 1804, Osage leaders traveled east to meet Thomas Jefferson in Washington City. Jefferson praised them as strong and noble but soon began pursuing policies that would strip their people of the very lands that had brought them such stature.

In 1808, the Treaty of Fort Clark, in present-day Jackson County, Missouri, near Fire Prairie, east of Kansas City. With a stroke of the pen and a few Xs, the Osage ceded some 50,000 square miles, much of it Ozark highland hunting country between the Missouri and Arkansas rivers. Yet, the Arkansas Osage, who roamed the White River and Spring River valleys, did not agree to this treaty. They resisted, and skirmishes flared.

By 1817, the violence grew so severe between Osage hunters and incoming Cherokee settlers that the United States built Fort Smith at the confluence of the Arkansas and Poteau rivers. This fort wasn’t just about keeping the peace; it was about cementing U.S. authority on the frontier.

Meanwhile, the Cherokee were on the move. Beginning in the late 18th century, Cherokee families trickled into the Ozarks, often with Spanish approval, and they served as buffers against the Osage.

By the early 1800s, hundreds had established settlements along the White River, the Arkansas River, and in the valleys stretching toward Batesville and present-day Marion and Baxter counties. The land reminded them of their Appalachian homeland. The Ozark hills were excellent reserves for hunting, fertile bottomland for corn, and room for cattle and hogs. By 1812, more than a thousand Cherokee lived in the Arkansas Valley, many traveling up the White River to hunt and trade.

The Quapaw and Delaware also had deep ties to the White River country. The Quapaw, native to Arkansas, welcomed Cherokee families for a time, while Delaware villages sprang up along the White’s tributaries, including the Strawberry and the Black rivers. The Shawnee, some settling near what is now Yellville, originally known as “Shawneetown,” became crucial cultural middlemen, bridging Cherokee, Osage, and even white settlers. Shawnee Territory also encompassed most of Ozark and Douglas counties in Missouri, and a few settlements in the Arkansas, White River Valley. Yet every year, more hunting and farming grounds were lost to treaties signed under pressure in faraway towns.

Amid this swirl of tribal migrations and federal maneuvering, a young Tennessean named John Hardeman Walker stepped into history. Moving into the Bootheel in 1810, Walker built his homestead near Little Prairie (modern Caruthersville, Missouri). When the New Madrid earthquakes of 1811–12 devastated the region, many families fled. Walker stayed put, ranching cattle and quietly expanding his holdings.

Walker’s persistence later paid off: when Missouri applied for statehood in 1818, the proposed border at the 36°30′ line would have excluded the Bootheel. Walker convinced Congress that the region was tied culturally and economically to Missouri’s river towns, not to Arkansas. As a result, the southern border was redrawn, dipping down and westward before bending north at the St. Francis River. Without Walker, the Bootheel might well have belonged to Arkansas today.

But state lines on a map meant little to the Cherokee and Osage locked in conflict in the White River Valley. In 1817, a bloody Cherokee raid on Osage villages killed more than eighty and captured a hundred more. Stories of Osage revenge raids carried fear into cabins from Batesville up through the White River Valley into modern-day Baxter and Izard counties. Settlers in what became Izard County reported hiding in makeshift forts and stockades whenever word of Osage war parties spread.

The U.S. government’s solution was treaty after treaty. In 1817, the Cherokee were promised 3 million acres between the White and Arkansas rivers in exchange for lands back east. That meant the Cherokee now legally held much of north-central Arkansas, including valleys of the White, Strawberry, and Black rivers. But “permanent” land proved temporary.

By 1824, pressures from white settlers, combined with continued hostilities with the Osage, pushed the Cherokee west again. In 1828, they relinquished their Arkansas lands altogether for territory in present-day Oklahoma.

For the Osage, the end came just as swiftly. By the 1820s, they had ceded nearly all their Missouri and Arkansas lands, retreating westward into Kansas. In 1837, militia forces cleared the last Osage families from Spring River, closing the chapter on centuries of Osage presence in the White River highlands.

Another layer needs to be added to this mix by understanding how the U.S. Government decided to enforce treaties and attempt to bring about peace as white settlers moved into the western region of the Ozarks.

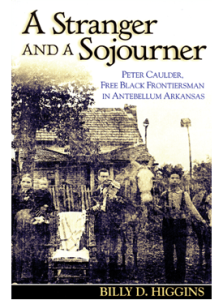

Fort Smith, Arkansas, was established to enforce treaties between Native Nations and to keep peace in the wild frontier. Among the soldiers stationed there were free Black veterans of the War of 1812, originally from Marion County, South Carolina. These men had gained their military experience fighting against Osage warriors and were later settled along the White River by 1826, in what is now Oakland, Arkansas. In a twist of irony, the land they made their home would eventually bear the same name as their birthplace, Marion County.

Their story is preserved in the book A Stranger and a Sojourner: Peter Caulder, Free Black Frontiersman in Antebellum Arkansas by Dr. Billy D. Higgins. This book details the remarkable lives of free Black frontiersmen such as Peter Caulder and David Hall, who carved out a place for themselves in northern Arkansas during a turbulent era. Their resilience adds another layer to the story of the Ozarks, where treaties, tribal conflicts, and the struggles of freedom all converged.

The echoes of these displacements still linger in the Ozarks. Place names, old trading paths, and unmarked burial grounds whisper the stories of those who lived here before the counties were drawn, before state lines were debated, before surveyors cut the land into townships and ranges. When we walk along the White River or pass the fields of the Bootheel, we are moving across a landscape layered with treaties, migrations, and memories, where men like John Hardeman Walker shaped borders, and nations like the Osage and Cherokee lost homelands.

The Louisiana Purchase was celebrated as Jefferson’s masterstroke, but in the Ozarks it marked a turning point, the beginning of the end for Native power and the dawn of an American frontier, where forts, farms, and state lines replaced hunting grounds, tribal boundaries, and ancient ways of life.

A big thank you to our friends at Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company. Their ongoing support is what helps 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨 echo through the hills with the true stories of the Ozarks, stories you won’t find in your average history book. It’s partnerships like theirs that keep our heritage alive and well, one story at a time.

Next time you’re in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and his incredible team. They’re helping to preserve local history with heart and hometown pride.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩s