Welcome to 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨 as Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson rediscover the remarkable journey of Sam and Alice Mason. Their story is one of resilience, love, and the unbreakable spirit that defined a family's path from slavery to freedom in the heart of the Ozarks.

First, we want to draw attention to all the farmers and landowners in the Ozarks who still maintain abandoned cemeteries on your property and say Thank You! In the past couple of weeks in Baxter County, Tink Albright invested her own money to protect the Messick Cemetery, one of the oldest in the county. Located along the Trail of Tears, a section of the Old Military Road, on what is now known as Tucker Prairie or Tucker Flats, this historic site is a testament to the region's rich past. No one twisted her arm to do it; Tink's dedication is a shining example of community stewardship.

If you happen to have an abandoned cemetery on your property and need some ideas, get in touch with Vincent Anderson to brainstorm solutions and preserve these important pieces of our shared history.

Sam & Alice Mason Story

In the past, we have briefly mentioned Samuel Mason and his wife Mary “Alice” Ridgeway Mason, the only African American family living in Cotter in 1908. Today, we will connect the remaining fragments of Sam and Alice's life and their connection to the Ozarks.

Alice was born in slavery and raised near Black Oak in Weakley County, Tennessee. According to the 1860 U.S. Slave Census, William Alexander "W. A." Ridgeway housed two young and unnamed black children in Weakley County, Tennessee. Most likely, Alice is the 4-year-old female slave child, and the boy, probably her brother, Joseph Ridgeway, was 2 years old.

By 1870, Alice and her brother, Joseph, were working as servants on the W. A. Ridgeway farm in Tennessee. Eventually, in the 1870s, the Ridgeways moved to the Ozarks. In 1880, Alice and Joseph were working as servants on a farm for Thomas Ridgeway, son of W. A. Ridgeway, in Sharp County, Arkansas.

Samuel "Sam" Mason was about 5 or 6 years older than Alice, and he was also born into slavery in Georgia about 1855. By 1860, Sam was living in La Crosse, Izard County, Arkansas, and he grew up on the Samuel Jefferson Mason farm. The 1860 Slave Census most likely reflects Sam and maybe his mother at age 23, listed as a 23-year-old female black and a 4-year-old male black (Sam?).

After the Civil War, there is no record showing Sam Mason, the Freeman, listed in Izard County in 1870. But in 1880, Sam was boarding with the Garner family in the La Crosse (Pronounced Lay Cross) Township, in Izard County. According to the U.S. Census, Sam Mason is listed as a farm laborer, and he can read and write.

On November 30, 1881, Sam and Alice went to the Izard County courthouse in Melbourne, Arkansas, and secured a marriage license. Two days later, Sam married Mary "Alice" Ridgeway on December 2, 1881, in Izard County, Arkansas.

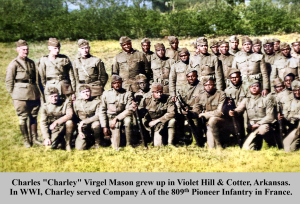

Eight years later, while living in Violet Hill, Arkansas, Sam and Alice had their only child who lived to adulthood, Charles "Charley" Virgel Mason, on February 15, 1890. Charley grew up in Violet Hill, Arkansas, and he also learned to read and write.

As Charley grew up, his father, Sam, worked as a carpenter and a shoemaker. Sometime after 1901, and the building of the railroad on the White River, Sam moved his family to Cotter, Arkansas.

The town of Cotter, Arkansas, sprang up in 1902 along the White River Railway, a project that brought both opportunity and upheaval to Baxter County. By the time the town incorporated in 1904, its population had already reached 600, and the establishment of the railroad’s division headquarters transformed Cotter into a booming hub. The promise of work attracted laborers from beyond the Ozarks, including African Americans who had been employed in large numbers during railroad construction. As the Cotter Courier observed that June, many black workers “remained” in the county after the line reached Cotter.

Yet from the town’s earliest days, local sentiment toward African Americans was far from welcoming. Arkansas Governor Jeff Davis (D) visited Cotter in 1904 and used his platform to denounce racial equality, stoking prejudice in a community where hostility was already simmering.

By 1905, the Cotter Courier was reporting that a “strong feeling” against black families was spreading through Cotter and Baxter County, even predicting that black residents would soon be gone altogether.

In 1906, matters came to a head. On April 6, the Cotter Courier ran a blunt editorial titled “Too Many Negroes,” which not only called for black residents to leave but also hinted at “drastic measures” to ensure their removal.

A few weeks later, seven African Americans were run out of town, leaving fewer than a dozen. Then, on August 24, after a fight between two black men, the white citizens of Cotter made what they called a “clean sweep.” Nearly every African American in the town was driven out in what became known as the Cotter Expulsion, except for Sam, Alice, and Charley Mason.

The Expulsion of 1906 remains a stark reminder that the prosperity the railroad brought to Cotter was shadowed by deep racial injustice. While the tracks carried progress through the Ozarks, they also carried with them the prejudices of an era that once drove an entire community into exile.

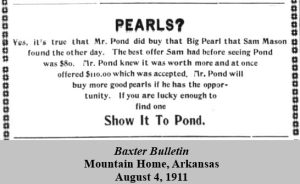

The week of July 17, 1908, was a memorable time for the Mason family. Many families were having trouble and financial distress was still on the minds of many people with the U.S. Bank Panic in the prior year of October 1907 which led to a nationwide economic depression. Due to the current drought, many people were searching for extra income, and some were using the White River as a resource. Sam Mason was no different as he culled for mussels along the banks of the White River, and he discovered a substantial-sized pearl. Sam proved himself to be a pretty great pearl hunter on the banks of the White River. One pearl netted Sam $110. In today’s value, it would be close to $4,000.

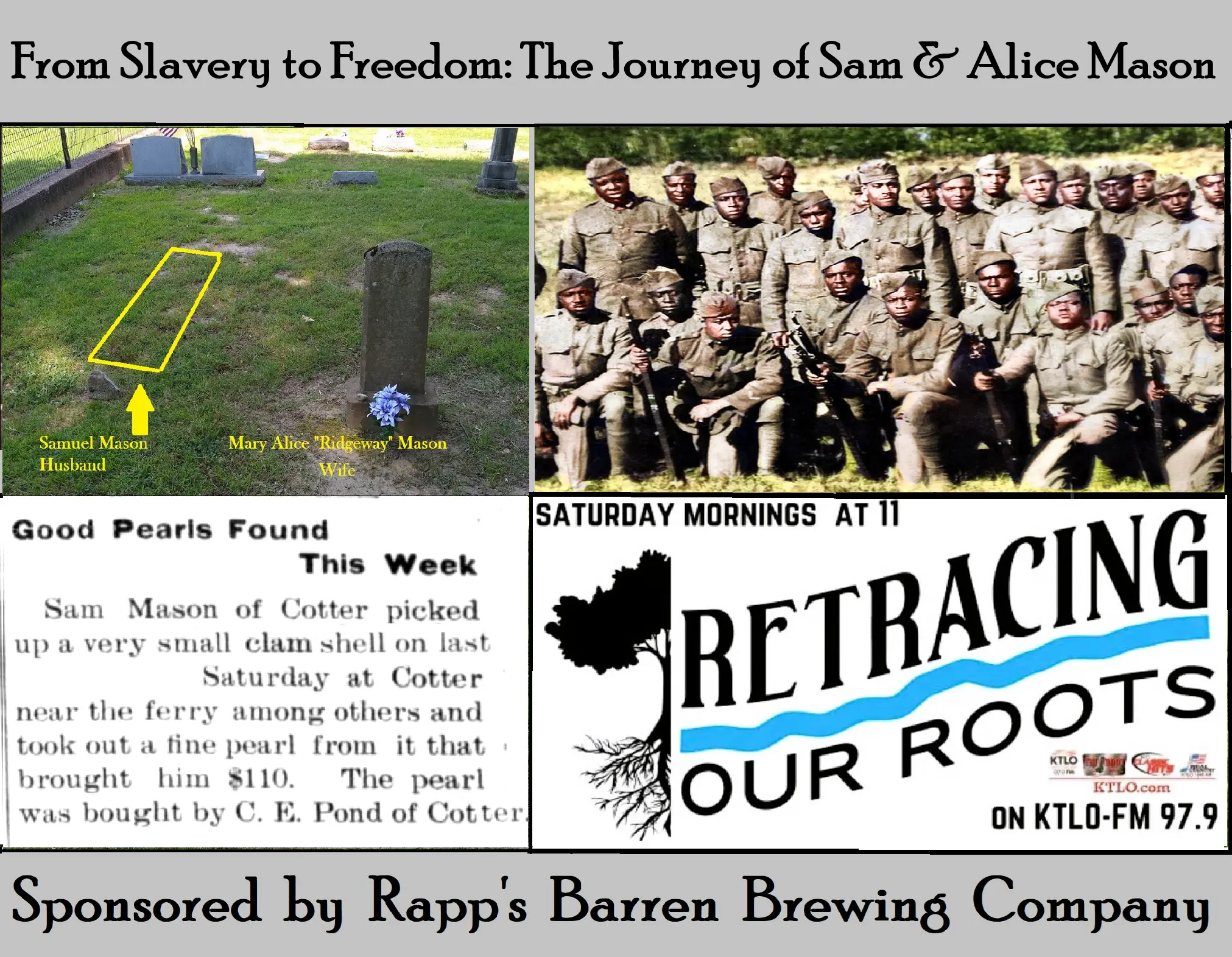

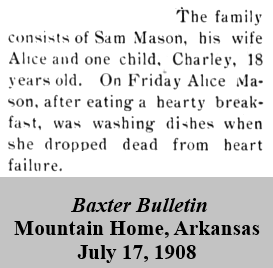

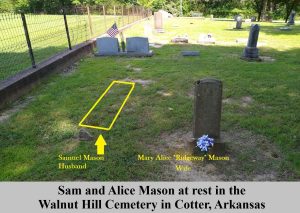

While newspapers carried the news of Sam's discovery, the same newspapers displayed saddening news for the Mason family. The following day, Mary “Alice” Mason passed away from heart failure after washing the morning’s breakfast dishes. The Cotter ladies assisted in arranging Alice's body for burial, and a procession made its way to the Walnut Hill Cemetery. People stood on the edge of the sidewalks and children cried, and Alice was laid to rest.

Sam remained in Cotter with his 18-year-old son, Charley. The next year, in 1909, Sam and Charley moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma.

In the following year, the 1910 Census records Charley living in Tulsa, Oklahoma, renting a room, and working as a hod carrier (brick carrier) for a construction company.

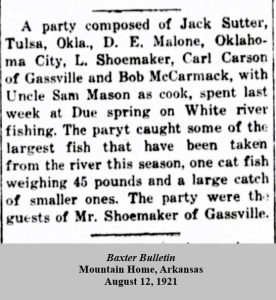

Sam Mason returned to Baxter County and the White River Region to live. We do not know the why or the reasoning behind his decision. In 1918, we find Sam is doing well according to a Baxter County Farm Demonstration Survey, and he is known for feasting on the White River's bounty, and he works as a popular White River cook preparing a bounty for fishing parties guided through the area.

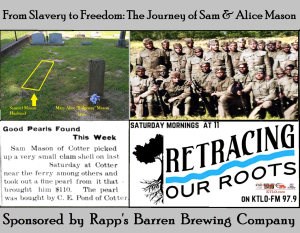

Eventually, Charley persuaded his father, Sam, to move to Tulsa and live with him and his wife, Wilma. During World War I, Charley registered for the draft. On his registration card, we can see Sam is still living with Charley and his daughter-in-law at 206 North Frankfort in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Once World War I commenced, Charley was called into active duty, and he was deployed with Company A of the 809th Pioneer Infantry and served in France.

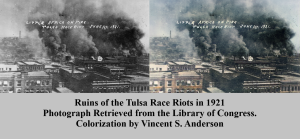

After Charley served his term in the Army during World War I, he returned to Tulsa, Oklahoma. These next few years would be troubling and pivotal years for the Mason family while living in Tulsa. It was during this time that the Tulsa Race Riots commenced. From May 31 to June 1, 1921, White residents attacked Black residents and destroyed homes and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. There were as many as 300 deaths in the mayhem and violence; it was called the Destruction of Black Wall Street. The Mason family from Baxter County lived in the Greenwood District of Tulsa during the Race Riots. Their address: 114 N. Greenwood Street in Tulsa.

Soon after the Tulsa Riots, Sam Mason travelled back to Baxter County, and he can be found cooking fish on the White River. Apparently, Sam was still well known for his fried fish on the banks of the White River in the Cotter, Arkansas, area.

There are still remnants of the Mason family's lives we have not pieced together yet. Nevertheless, the pieces that remain are beginning to shine a light on their journey, hardships, and joys. As a historian, I have collected these small fragments over the years, and I thought it would be appropriate to tell as much of the story as I know. We are still looking for Charley's burial place and more pieces of his life.

It is indeed amazing to look back at the hearty people who endured traumatic times and circumstances and witness their resilience. Sam and Alice Mason were people of unyielding strength and unwavering courage. Despite the numerous challenges they faced, from the horrors of slavery to the racial violence of their time, they persevered with dignity and grace. Their journey is a testament to the human spirit's ability to endure and thrive against all odds.

Sam and Alice's story is one of love, perseverance, and the pursuit of a better life. They built a family and a future in the face of immense adversity, and their legacy lives on through their son, Charley. The Masons were not just survivors; they were builders, contributing to their communities in meaningful ways.

Sam's skill as a carpenter and shoemaker, and his knack for pearl hunting, show his resourcefulness and adaptability. Alice, though her life was cut short, was a pillar of strength and support for her family.

The Masons' experience in Cotter, Arkansas, highlights the complex and often painful history of racial relations in the United States. Despite the hardships and the eventual expulsion of African Americans from Cotter, the Masons were remembered for their testament to their positive impact on the community. Their story is a reminder of the resilience and dignity of those who have been marginalized and persecuted throughout history.

As we reflect on the lives of Sam and Alice Mason, we are inspired by their strength and the enduring power of the human spirit. Their legacy serves as a beacon of hope and a reminder that even in the darkest of times, there is always room for resilience, love, and the pursuit of a better tomorrow. Rest in peace, Sam and Alice Mason, your story will continue to inspire and educate future generations.

Rest in Peace Sam & Alice Mason.

Rest in Peace.

A big thank you to our friends at Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company. Their ongoing support is what helps "Retracing Our Roots" echo through the hills with the true stories of the Ozarks, stories you won’t find in your average history book. It’s partnerships like theirs that keep our heritage alive and well, one story at a time.

Next time you’re in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and his incredible team. They’re helping to preserve local history with heart and hometown pride.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨