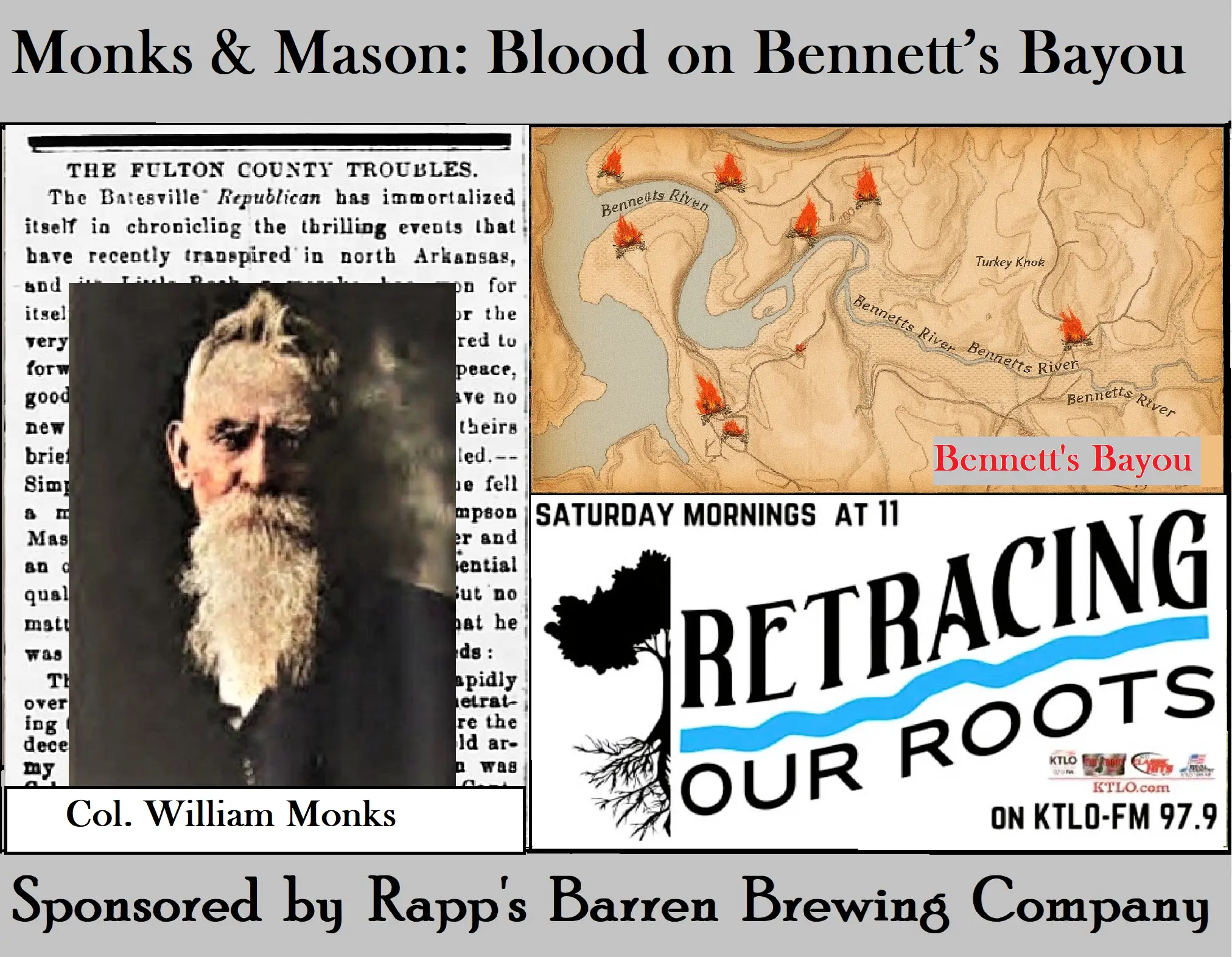

Monks, Mason & Blood on Bennett’s Bayou

Welcome to Retracing Our Roots as Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson rediscover two influential men in the Bennet’s Bayou area after the Civil War. Today, we’re taking you into the turbulent, dangerous world of the Ozarks in the years after the Civil War.

Two men, Colonel William Monks of Howell County, Missouri, and Simpson Mason of Fulton County, Arkansas, stood shoulder to shoulder for the Union… long after the shooting war ended.

It would cost one of them his life.

In the turbulent aftermath of the Civil War, few figures embodied the perilous transition from conflict to peace quite like Simpson Mason. A bootmaker by trade, Union scout by necessity, and civil servant by conviction, Mason's life and brutal death paint a vivid picture of Reconstruction-era Arkansas—where loyalty to the Union could still get you killed.

Very little is known of Simpson Mason’s early life. He was a bootmaker by trade, and the 1860 census finds him living with his sister's family in Union Township, Fulton County, just a few miles south of Salem, Arkansas. At about 39 year-old, he was a South Carolina native raised in Georgia, unmarried, and childless. He owned modest real and personal property, totaling just over $1,200; it was a respectable amount for the time. But how or when he arrived in Arkansas remains a mystery.

Mason’s life would take a decisive turn with the Union victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862. As the Federal Army of the Southwest pushed into northern Arkansas, Mason aligned himself with Col. William Monks, a fierce Unionist who straddled the Arkansas-Missouri border.

William Monks had a reputation of going against the grain of Confederate sympathizers. Many of these sympathizers called Monks the most hated man in southern Missouri.

Captured by Rebels in 1861, he escaped to Union lines in Springfield and led guerrilla operations with the Sixteenth Missouri Cavalry. His men hunted down bushwhackers, and Monks claimed to have killed more than fifty in the war’s final months. Monks was bold, brash, and not one to forgive. Even after the war, he spent years suing wartime enemies and their heirs.

His service didn’t go unnoticed. In 1864, Mason was elected to the Arkansas House of Representatives, serving during the state’s fledgling Unionist government. By early 1865, Mason was a militia captain under Governor Isaac Murphy, leading Unionist refugees back home. Friends warned them not to return.

Monks objected to the Unionists who were worried about returning to Fulton County, Arkansas. Monks would growl say, “Damn a man that is afraid to go back and enjoy the fruits of his victory.”

After the war, both Monks and Mason became agents for the Freedmen’s Bureau, one of only eleven such posts in the state of Arkansas. Their job? Protect loyal Union citizens, freedmen (former slaves), and refugees from a Confederate resurgence.

It was dangerous work, as Mason’s enemies never forgot his wartime service.

In June 1865, Mason’s militia patrolled the Bennet’s Bayou region and ended up executing two ex-Confederate bushwhackers. The killings brought murder charges. The charges were later dropped, but this painted a target on Mason’s back.

Violence escalated across the Ozarks. Unionists were hunted. On Christmas Day, 1867, news spread that Uriah Douthit, an advocate for African American rights, was gunned down near Evening Shade, Arkansas. Northern Arkansas was still a dangerous place to live.

By spring 1868, the Ku Klux Klan had arrived in Northern Arkansas to push back against Monks and Mason. In Bennett’s Bayou area of western Fulton County, Jesse Harrison Tracy led a chapter of the Klan bent on destroying Reconstruction. Mason fought back, joining the Union League of America.

But on September 19, 1868… the Klan struck first.

While riding to register voters at Bennett’s Bayou, Mason was ambushed. Shots rang out. He fell from his horse. Simpson Mason was dead before he hit the ground.

News reached Monks in Missouri. He saddled up with a militia unit, rode into Fulton County, seized suspects, destroyed the Tracy farm, and, according to some reports, some prisoners were tortured for answers.

While transporting two men, Uriah Bush and Joseph Tracy, a masked gang attacked. Bush was executed on the spot. Tracy was spared… and later released.

No one was ever tried for Mason’s murder. His grave remains lost to history.

Monks survived Reconstruction and reinvented himself as a formidable defense attorney and special judge in Southern Missouri. Monks was still feared and despised in the courtroom just as he was on the battlefield.

Late in life, Monks began attending a Christian Church, committed his heart to the Lord, and became a member of the church. One Rolla, Missouri paper attempted the last word and quip on Monks’ religious conversion by saying Monks came to the Lord and got religion, “…just despite the devil.”

Two men.

Bound by the Union cause.

One died by ambush.

The other lived long enough to make peace with Heaven.

A big thank you to our friends at Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company. Their ongoing support is what helps Retracing Our Roots echo through the hills with the true stories of the Ozarks, stories you won’t find in your average history book. It’s partnerships like theirs that keep our heritage alive and well, one story at a time.

Next time you’re in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and his incredible team. They’re helping to preserve local history with heart and hometown pride.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨