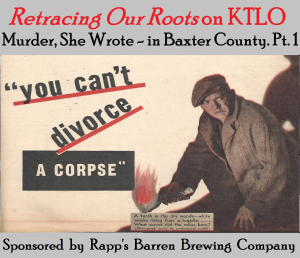

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨.

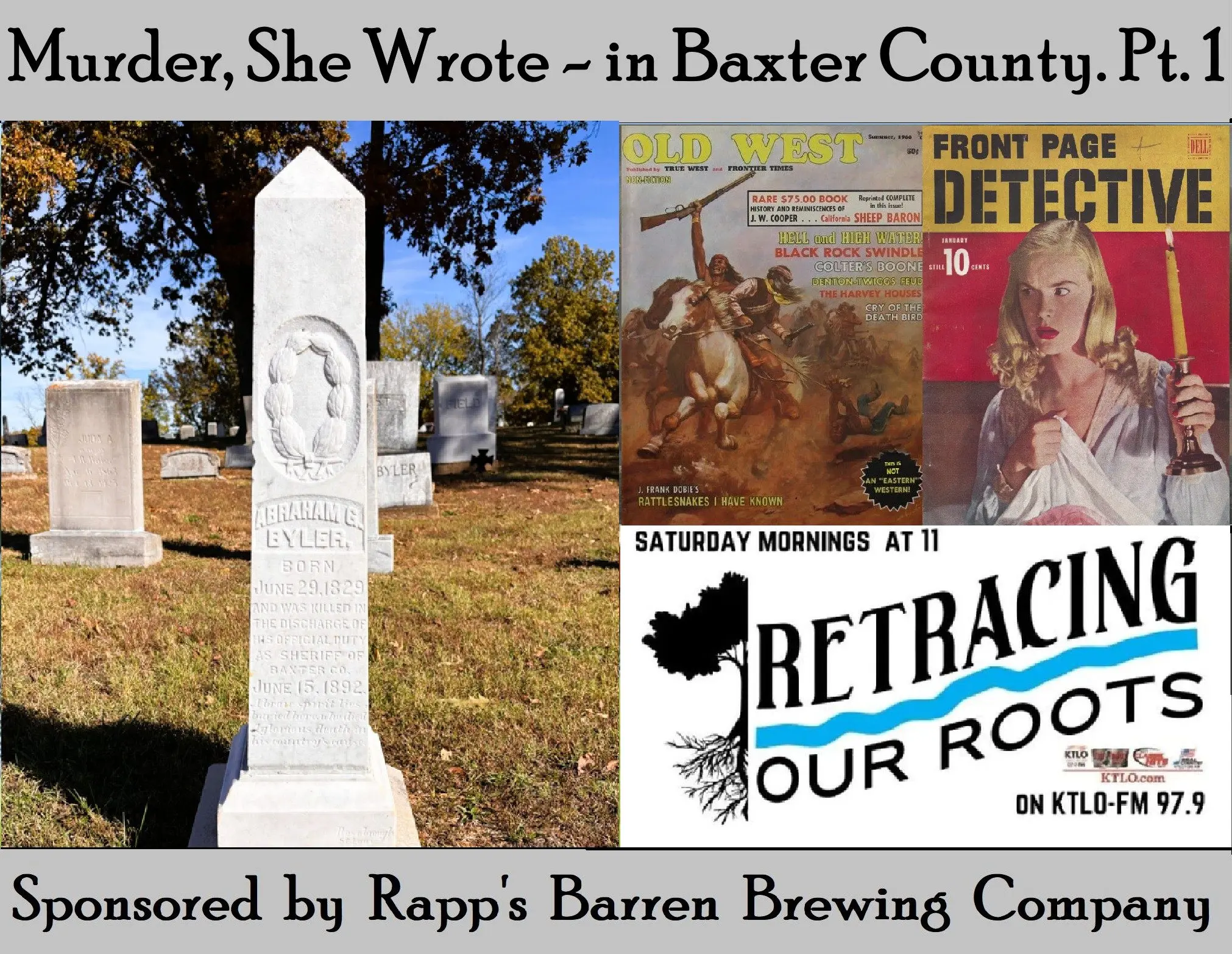

Murder, She Wrote in Baxter County – Part 1

Welcome to another fascinating episode of 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨 with Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson. Today, we have a special guest joining us for the next two weeks: Maryanne Edge. Maryanne has chronicled the murders of Baxter County from the 1880s all the way up to 1999. Her two-volume book is called, “Was it Murder?” They are both available at the Baxter County Historical Museum, and they can be checked out at the Baxter County Library.

Caution: these stories are not for young children or the faint of heart.

The Graves Children - March 30, 1886

On a cold March night in 1886, a quiet Baxter County was shaken by one of its first and darkest crimes. Ben Graves, living on the Strait farm south of Mountain Home, was seized by a violent fit of insanity that ended in the death of his two children.

According to The Baxter Citizen (April 2, 1886), Graves woke his wife around midnight, warning her that he would kill the children, and her too if she interfered. He then beat his two-year-old to death, while his wife fled barefoot into the night for help. When neighbors Mr. Strait and Mr. Knight returned with her, they found one child dead on the floor and the infant burned upon the fire.

Graves fled to the woods but was captured the next morning and jailed. The coroner’s inquest found he had shown signs of insanity earlier that day, claiming later that God had commanded the sacrifice “for the sins of the people.”

The crime outraged the county, though Graves had been considered a decent, affectionate man before his breakdown.

As The Mountain Echo later reported (March 28, 1887), Ben Graves was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to twenty-one years in the penitentiary. It was a grim end to a tragedy that haunted Baxter County for years to come.

In our next story, we will detail the family feud that took place in Gassville, Arkansas. Folks, a lot of things happened in Gassville.

Denton-Twiggs Feud (1891)

At one time, these families worked together in a community as ranchers. But there was a pretty big falling-out between these families, and it literally divided the small town of Gassville. Members of the community aligned their loyalties to the Dentons or the Twiggs, and they displayed their loyalties to each faction by lining up against each other on either side of the main road in Gassville.

Everything started coming to a head in August of 1891, when the long-simmering feud between John Twiggs and the Denton brothers came to its violent end in Gassville, Baxter County, Arkansas. What began as a rivalry and rumor turned, before noon, into a gunfight that left one of the county’s best-known men dead on the wooden steps outside Cox & Denton’s store.

For months, bad blood had brewed between Twiggs and Lee Denton. When the store was mysteriously set on fire earlier that summer, Twiggs accused Lee of the deed. Lee denied it bitterly, and in the weeks that followed, both men exchanged harsh words around town. Twiggs claimed to have seen Lee sneaking around at night; Lee countered that he was only watching Twiggs, whom he accused of moral wrongdoing. Each insult deepened the divide until the tension in Gassville could have been cut with a knife.

On the morning of August 21, John Twiggs walked into Cox & Denton’s store with purpose in his eyes. Lee stood behind the counter, his brother Eng nearby. Witnesses said Twiggs cursed both men, calling them cowards and liars. “I’ll see you later,” he spat, turning as if to leave. At that moment, Eng gave a brief nod, and two pistols fired almost at once.

Twiggs stumbled through the doorway, reaching for his own gun. He made it only a few steps before collapsing near the block step outside. A bullet had torn through his brain. Two young women, Dora Flippin and Belle Mooney, whom Twiggs had been courting, ran to him as he fell. He died six hours later, without a word.

The Dentons were arrested but soon released on bond. The coroner ruled the killing manslaughter, a verdict that divided the community. Some swore it was self-defense; others believed the Dentons plotted to silence Twiggs, who knew too much about the fire.

Both sides were well respected. Eng Denton was a businessman and churchman, Twiggs a fearless bachelor with friends and enemies alike. The tragedy left Gassville reeling. It was a quiet reminder of how pride, suspicion, and anger could ignite as swiftly as gunpowder in the rough hills of Baxter County.

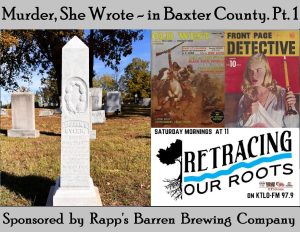

The Assassination of Sheriff Abraham Byler (1892)

During Baxter County’s history, we have lost three sheriffs to gunfire and one who passed away while in office. In the assassination of our first sheriff, we find it on the tail of our Denton-Twiggs Feud. Unfortunately, its detail rests in the outflow of the Denton-Twiggs Feud that erupted in Gassville, Arkansas.

It was a summer evening, June 15, 1892, when Sheriff A.G. Byler of Baxter County answered the call of both courage and conscience. A posse from Mountain Home arrived in Gassville to capture Jesse B. Roper who was wanted for carrying a pistol and suspected of a recent robbery. Roper had already defied Officer Combs at Gassville, drawing his gun and swearing he’d never be taken alive.

Byler, true to his oath, gathered twenty men and rode toward the home of Capt. W.A. Twiggs, two miles southeast of town, where Roper was believed to be hiding. The men quietly surrounded the place. Byler and Deputy Livingston approached the house, calling for entry

Byler then moved toward the nearby smokehouse. As he rounded the northwest corner, Roper, lying in wait, pushed the barrel of a Winchester rifle through a crack in the wall and fired. The bullet struck Byler in the upper abdomen. He staggered, turned half around, and Roper fired again. Both shots sealed Byler’s fate. The sheriff fell to the ground, crawling a few feet before asking for water. Within minutes, he was gone.

Deputy Livingston narrowly escaped the same fate. Outside, chaos erupted. Roper bolted from the smokehouse, sprinting across a field. He shot Dr. J.H. Lindsey’s horse dead, wounded Dr. J.B. Simpson’s, and traded fire with the doctors, who returned shots from behind their fallen mounts. A mile farther, Roper met L.E. Hopper, shot him in the leg, and was himself wounded, though not enough to stop him. Roper vanished into the Ozark hills before nightfall.

Joe Twiggs reportedly stood in the doorway of the house with a rifle, daring any man to enter until Roper was safely gone.

A wanted poster was soon posted with a $1,000 reward for Roper. The following information describes Roper:

WANTED

“By authorities of Baxter County, Arkansas, Jesse Roper who murdered the Sheriff of Baxter County, A.G. Byler on the 15th day of June 1892. Jesse Roper is about six feet high, weighs about 160 pounds, light complexion, light hair, cut pompadour in front, light mustache, blue eyes, downcast look, small mole or tit on one cheek, age 26. He wears a No. 37 coat and a No. 8 shoe. Roper will probably be armed with a Winchester rifle and pistols. There will be a $1,000 reward paid by our citizens for the arrest and delivery to the authorities of Baxter County. The governor will also offer a liberal award.

John W. Cypert,

County Judge”

The murder shocked both Arkansas and Missouri, where veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic publicly denounced rumors that they were sheltering the fugitive.

Sheriff A.G. Byler was remembered as a brave and upright officer, and his goodness was matched only by his fearless devotion to duty. His death marked one of the darkest days in Baxter County’s early history.

Over the years, information on the capture, incarceration, and suicide of Roper occurred repetitively over the years. By different accounts, Roper committed suicide three different times. It is a mystery to Roper’s true fate here on earth.

The 1934 Bumps Tragedy

The Wrench in Her Hand

In early March of 1934, a grim story gripped Baxter County. E.M. Bumps, a 68-year-old man known around town, was dead from blows to the head. He was struck by a monkey wrench in the hands of his own wife, Harriet.

The Bumps ran a small tourist camp on the edge of town, where travelers could find a meal, a beer, and a bit of music from the dance hall next door. By all accounts, they were a friendly couple, until whiskey changed Mr. Bump’s disposition. When sober, he was kind and doting. But when alcohol took hold, his temper was violent.

According to Harriet Bump’s statement to The Baxter Bulletin, her husband had been drinking heavily for several days. One night, in a drunken rage, he threatened to kill her, their young daughter, and himself. Terrified, she hid his revolvers and had his shotgun carried off to the barn. But by Friday evening, the violence returned.

Around six o’clock, E.M. Bump came at her with a butcher knife. The door was locked with no escape. On the floor nearby lay a monkey wrench. In desperation, she seized it and struck him several times in the head.

He was rushed to the hospital but never regained consciousness. He died that night from a fractured skull.

Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Kent Jackson issued a warrant for first-degree murder, but when the hearing was held before Justice of the Peace J.C. Watson, the evidence told a clearer story: self-defense. After hearing seven witnesses, the court dismissed the charge, and Mrs. Bumps was released.

When asked afterward what she would do next, Harriet said she planned to return home and keep running the tourist camp. Despite everything, she spoke kindly of her late husband—saying their life together had been good except for the times when liquor darkened his mind.

The Frank and Lela Melton Tragedy (1935)

The Morning She Pulled the Trigger

It was a quiet Sunday morning, September 29, 1935, near the small community of Cartney, Arkansas. Inside a modest cabin tucked among the hills lived Frank and Lela Melton, a young couple whose eighteen-month marriage had been anything but peaceful. By dawn that morning, the violence that had haunted their home came to its final breaking point.

Lela was just twenty years old, a small, fair-haired woman weighing barely 117 pounds. Frank was a big man, 190 pounds, only twenty-four, but known to drink hard and fight harder. The night before, he had beaten Lela three times. Once it was with a broom handle, twice with his belt, and then told her that if he woke up first in the morning, he’d kill her, her father, and her teenage sister, Lottie.

When daylight arose over Baxter County, Lela awoke before him. She looked over at her sleeping husband and remembered his words. In the corner of the room stood their single-barrel shotgun. Quietly, she loaded it, stepped closer, and fired a single shot into his forehead.

The blast was fatal; it was so close it nearly destroyed the top of his head. The young wife then dragged his body about thirty-five yards behind the house to a gully and covered it with leaves. For days, she kept silent, telling neighbors that Frank had left her. But when two local boys, Jim Booth and Hubert Casteel, stumbled upon the body, the truth began to unravel.

When questioned, Lela calmly confessed. “I knew they’d find him,” she said, “and made up my mind to tell the truth when they asked me.” She showed officers the bruises still fresh on her body. “I’ve taken twelve beatings from him,” she told them.

At first, she was held in the Baxter County jail, then moved to Marion County, where there were quarters for women. She seemed strangely cheerful: singing, laughing, and showing little concern for her fate. Newspapers described her as “a pretty blonde wearing a 10-cent diamond ring her husband had bought her two weeks before she killed him.”

Over the next several months, her case wound through the courts. Doctors examined her and declared her insane, and she was sent to the State Hospital for Nervous Diseases in Little Rock. But after weeks of observation, they pronounced her sane and returned her to jail to await trial.

Her first trial, in March 1936, ended with a hung jury, half believed she should be freed, the other half voted for a conviction of second-degree murder. Prosecutors prepared to try her again, but Lela, weary of confinement and expecting another child, agreed to plead guilty to “involuntary manslaughter.” The court accepted the plea and sentenced her to one year in the Arkansas penitentiary.

When asked why she chose to plead guilty, she replied simply, “I’d have to stay in jail until the September term if I didn’t, and by then, I’d have nearly served my sentence.”

It was a pitiful story of a young woman driven past the edge by fear and abuse, of a marriage built on violence, and of justice meted out in a time when women like Lela often had nowhere to turn but the shotgun in the corner.

The Merrow Murder Case (1946)

The Bones in the Brush Pile

In the summer of 1946, a grim mystery began to unfold in the hills southeast of Mountain Home. Fifty-year-old Vedah Merrow had been missing since June 9. Her husband, Leon A. Merrow, age 55, told conflicting stories: first that she died, then that she ran off with another man. But when neighbors reported a burned brush pile on the Merrow farm, suspicion began to rise.

On Saturday, June 22, Sheriff Ernie Gentry and Patrolman W.T. Bowling discovered a charred skull, fragments of bone, and several buttons in the ashes of that pile. Later, neighbor Russell Reed, with two of his granddaughters and Harvey Smith, found more teeth, a hairpin, and burned cloth, all near a puddle of dried blood.

It appeared the body had been cut in two and burned in separate heaps. The remains were examined by Dr. E.M. Gray, who concluded they were human. State police confirmed the same.

Vedah’s disappearance now looked like murder. She had been last seen alive on Sunday evening, June 9, when she and Leon left to plant tomato sets on their farm. Around dusk, nearby residents, the Pitchford family, heard a woman’s scream from that direction.

At the time, Leon had already left for Illinois, traveling alone on a train for which he’d bought two tickets to Decatur. Once there, he filed for divorce within a day of arrival, telling relatives inconsistent stories about his wife’s fate. Their doubts led them to contact Sheriff Gentry, who began the search that uncovered the grisly evidence.

Mr. Merrow was arrested in Decatur by Sheriff Emery Thornell and returned to Baxter County to face a charge of first-degree murder. During questioning, he admitted to burning the brush pile, but he claimed it contained only two dead pigs, not his wife.

Investigators found more damning clues: a gold dental plate with three teeth, identified as Mrs. Merrow’s buttons matching her dress; and scraps of women’s clothing in the ashes.

Curiously, among Vedah’s belongings was an old pamphlet from 1935, establishing the “First Church of Jesus Devine, the House of Prayer for All People” in Decatur, Illinois. It was signed by Rev. Leon A. Merrow, Bishop. When questioned about it, he admitted, “I used to be a preacher.”

Mr. Merrow was sent to the State Hospital in Little Rock for a mental evaluation, but doctors found him sane. He returned to Baxter County to stand trial.

In September 1946, the case went before a circuit court jury. Expert witnesses testified that the bones, teeth, and charred flesh found on the Merrow farm were human. The defense offered no solid proof to the contrary, maintaining that the remains were animal. The jury didn’t believe it.

On September 11, 1946, Leon A. Merrow was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in the Arkansas penitentiary.

The case shocked Baxter County. It was not just for its brutality, but for the strange calmness of its accused: a former pastor, a husband, a farmer, a man whose last attempt to cover up a crime went up in smoke.

𝐓𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐤𝐬, 𝐑𝐚𝐩𝐩’𝐬!

A special thank you to Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company for their sponsorship of 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨. Their continued partnership helps us share the real stories of the Ozarks, the kind you don’t always find in textbooks, but hear heart-to-heart across backroads and kitchen tables. It’s thanks to local supporters like Rapp’s that the voices of our past still echo through these hills.

The next time you’re in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and the whole crew. Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company is helping us pour heart back into our local history.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨