Retracing Our Roots

Ozark Prairies & Forests: The Original Estate

Welcome to Retracing Our Roots as Adam Rogers and Vincent Anderson, dive into the heart of the Ozark region, its people, places, and legacies. In today’s episode, we unearth the Ozark Prairies and Forests, not as mere scenery, but as the original estate of this storied land. We’ll trace the ecological memory of fire, the vibrant biodiversity of native plant and animal life, and the intricate relationship between Native American stewardship and frontier settlement that shaped this remarkable region.

Long before modern settlement, the Ozarks were a patchwork of prairies and barrens, each with its own character and story. These open landscapes, now largely overtaken by forest or farmland, were once vital to the region’s ecology and culture. Among them were:

- Kickapoo / Harris Bottom (Stone County, Arkansas)

- Rapp’s Barren (Baxter County)

- Tucker Flats/Barren (Baxter County)

- Cowan Barren (Marion County)

- Flippin Barren (Marion County)

- King Barren (near Bruno in Marion County)

- Baker’s Prairie (Harrison in Boone County)

- Kickapoo Prairie (Christian and Greene Counties, Missouri)

These prairies were not static; they were dynamic systems, shaped by natural forces and human hands, particularly through the use of fire.

The Ozark forests, dominated by hickory and oak, provided shade, shelter, mast crops for wildlife, and hardwood for human use. In the southern Ozarks, pine forests were harvested for lumber and turpentine, shaping local economies. These forests, maintained by fire and Indigenous stewardship, were dynamic systems. However, post-settlement land use, including fire suppression, led to significant ecological shifts, allowing species like red cedar to proliferate.

The Ozark prairies and forests were defined by key plant species that supported both the landscape and the livelihoods of those who lived here. Some of the noted species are:

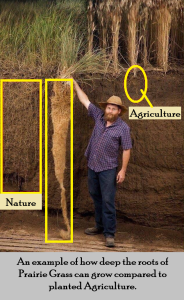

- Big Blue Stem and Little Blue Stem: Dominant prairie grasses that fed wildlife and thrived in harsh conditions.

- Gamma Grass: A soil anchor, preventing erosion and stabilizing the prairie ecosystem.

- Broomsedge: a transitional zone grass where grassland meets forest.

- Yellow and Purple Coneflowers: These vibrant wildflowers, still visible along roadsides and ditch lines, once painted the prairies in bold colors. Though still present, their abundance has noticeably declined, likely due to habitat loss and competition from invasive species.

- Pawpaw Trees: Their fruit was a prized resource for early pioneers.

- Sassafras Trees: Valued for their aromatic and medicinal properties, used in teas and tonics.

- Red Cedar: Once rare, now an invasive species due to the suppression of natural fires.

However, this native diversity faced challenges from invasive species. For example, Johnson Grass, introduced from eastern Asia or Turkey to South Carolina in the 1830s by Governor John Hugh Means, spread rapidly westward. By the late 19th century, it had overtaken native grasses across the Ozarks, disrupting the delicate balance of the prairie ecosystem.

The prairies and forests teemed with wildlife, each species a thread in the region’s ecological tapestry:

- Mountain Boomers: A vibrant yellow-colored lizard, unique to the Ozarks’ rocky prairies and bluffs.

- Elk: Once native, now reintroduced after centuries of absence, reclaiming their place in the ecosystem.

- Black Bear: Thriving in the forest-edge habitats, a symbol of resilience.

- Carolina Parakeet: Once a colorful presence, declared extinct in 1939 after the last captive bird, Inca, died in 1918 at the Cincinnati Zoo.

- Passenger Pigeon: Known for darkening the skies in vast flocks, the last of its kind, Martha, perished in 1914, also at the Cincinnati Zoo.

- Red Wolf: Although we did not mention this mammal in our radio show, it was once a key predator across the Ozark Plateau, balancing deer and rodent populations. By the mid-20th century, habitat loss, predator control programs, and hybridization with coyotes nearly eradicated this species from the region.

These species reflect the rich biodiversity once sustained by the prairie-forest balance, and the profound losses caused by its disruption.

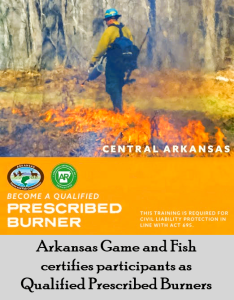

Fire was the heartbeat of this landscape. Ignited by lightning and human hands, it acted as a great equalizer, preventing any single species from dominating and enabling others to thrive.

Native Americans used fire with precision and purpose, not as a destructive force but as a tool for renewal. Prescribed burns served multiple functions:

- Renewing Grasslands: Fire returned nutrients to the soil, fostering vibrant prairie growth.

- Supporting Wildlife: Open landscapes created ideal grazing and foraging habitats.

- Preventing Forest Encroachment: Regular burns kept prairies from being overtaken by trees, maintaining ecological diversity.

This practice created a mosaic of habitats, sustaining both plant and animal life for centuries. Historical data underscores the frequency of these burns:

- In the Current River Watershed, fires occurred every 6.1 to 12.1 years between 1701 and 1820.

- Across much of the Ozarks, fire returned every 2.8 years until the mid-1800s.

These cyclical burns were part of a God-ordained rhythm, a dance of dormancy and renewal that kept the land fertile and balanced.

In the early 1900s, Arkansas launched a tick eradication campaign to combat disease, known locally as “ticking.” This initiative used fire, chemicals, fencing, and habitat manipulation to control tick populations. While effective in some respects, it disrupted native ecologies, accelerating the decline of open prairies and altering the region’s ecological balance.

The Ozark prairies and forests are more than land, they are a living testimony to the region’s history. They speak of fire’s role in fertility, the harmony of stewardship, and the balance between creature and creation. To conserve these spaces today is to remember rightly, to honor the original estate with humility and responsibility.

A big thank you to our friends at Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company. Their ongoing support is what helps Retracing Our Roots echo through the hills with the true stories of the Ozarks—tales you won’t find in your average history book. It’s partnerships like theirs that keep our heritage alive and well, one story at a time.

Next time you’re in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and his incredible team. They’re helping to preserve local history with heart and hometown pride.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨