White River’s Baptism into the Civil War

Welcome to another detail-packed episode of Retracing Our Roots with Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson. Before we begin our journey through the Civil War in the White River Valley, we want to revisit a previous episode: “A Cry from Wallace Knob.”

We’ve received multiple phone calls, visits, emails, and messages about the heartbreaking, and redemptive, story of Louise Maynard Adams. Although the book has been out of print, it will soon be available again at the Baxter County Historical Museum. It should retail for around $15.00.

Here’s an interesting sidenote about Louise’s father, Ralph Maynard, known by his nickname, "Snake." A gifted musician, Ralph loved to entertain crowds with his guitar. One song became a staple of his repertoire: Rattlesnak’in Daddy. Hence, his nickname Snake.

That song was first recorded in New York in 1935 by Blind Boy Fuller in a classic Delta Blues style. In 1951, the country music star Hawkshaw Hawkins recorded a version more in line with Texas Swing. You can hear his version here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3-aO-vb_S-k

Additionally, Missouri State University hosts the Max Hunter Folk Song Collection, which features Mrs. Ollie Gilbert of Mountain View, Arkansas, singing her Ozark version of Rattlesnak’in Daddy on August 27, 1969. Listen to her sing it here: https://maxhunter.missouristate.edu/songinformation.aspx?ID=854

The Civil War and Local Ties

Today, we begin our account of the Civil War in the Twin Lakes Area. It’s not a story that can be told in one sitting, but rather a woven tale of conflict, heartache, and hardship that deeply marked our region. As we trace these events, we’ll witness suffering on every side. Whether soldier or civilian, rich or poor, man, woman, or child—the war spared no one. This bloody conflict was an equal-opportunity devastator.

Many local men in northern Arkansas initially enlisted in the 14th Arkansas Infantry. The regiment was organized in the fall of 1861 with 939 officers and enlisted men, most of whom were recruited from northwestern Arkansas. Local men trained for this conflict around Pigeon Creek and along the North Fork of the White River.

The 14th Arkansas Infantry would go on to fight in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, also known as the Battle of Oak Hills, near Springfield, Missouri. Wilson’s Creek was the first major Civil War battle fought west of the Mississippi River and the site of the death of Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, the first Union general killed in action. The costly Southern victory on August 10, 1861, brought national attention to the war in Missouri. Today, Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield commemorates and interprets the battle within the broader context of the Trans-Mississippi theater.

The 4th Iowa Cavalry Comes South

Next, our narrative turns to a vivid memoir chronicled by William Force Scott, detailing the first bloodshed along the White River in Northern Arkansas. The account draws from official military records and Scott’s book, The Story of a Cavalry Regiment: The Career of the Fourth Iowa Veteran Volunteers: From Kansas to Georgia, 1861–1865.

The 4th Iowa Cavalry Regiment was dispatched from Camp Harlan in Mount Pleasant, Iowa, in September 1861, heading to Missouri and Arkansas. By March 10, 1862, training in St. Louis was complete, and the regiment, now mounted, was ordered over 300 miles to the northwestern edge of Arkansas.

Their first leg, about 100 miles to Rolla, Missouri, was fraught with hardship: inexperience, torrential rains, and impassable roads bogged them down.

From Rolla, they advanced through Waynesville and Lebanon, reaching Springfield, Missouri. After a brief stay, the men marched south along the Military Road, which passed the Wilson’s Creek battlefield. A few years later, this same road would be dubbed the Old Wire Road, thanks to the telegraph lines strung along its path.

On March 26, they were assigned as reinforcements at the Pea Ridge Battlefield (March 7–8, 1862). But upon arrival, Union General Curtis decided their presence was no longer needed, and the regiment was ordered to return to Springfield. The soldiers were struck by the eerie remains of battle: broken trees, charred structures, and countless fresh graves.

Back in Springfield, the 4th Iowa set up camp in tents west of town in Fort Campbvell, near present-day Campbell Street. Rain persisted, and the resulting mud made roads nearly impassable. While enduring poor conditions, the cavalry drilled, patrolled, and performed scouting duties. Illness soon swept the camp—spurred by exposure, poor rations, and contaminated water.

First Blood on the White River

On April 14, four companies of the 4th Iowa Cavalry broke camp in Springfield and headed south toward Forsyth along the Ozark Road. Although spring had arrived, intermittent downpours still made for soggy travel. The troops took note of blooming peach orchards, green pastures, and the rugged beauty of the Ozarks. Still, the Civil War had cast its die, and the White River region was on the brink of war.

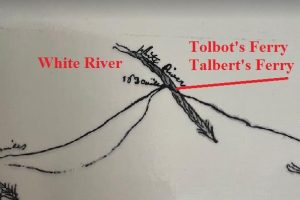

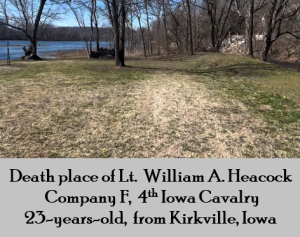

By this time, the 4th Iowa Cavalry found themselves squarely on the White River. The so-called “Butternuts” (Confederates) didn’t resemble regular soldiers. Lt. Heacock attempted to negotiate for the ferry peacefully, but the talks failed—the rebels considered themselves firmly at war. Heacock ordered his men to fire.

Someone on the Confederate side returned fire immediately. A single Minié ball struck Lt. Heacock in the forehead, killing him instantly on the Baxter County (eastern side) of the White River.

First Sergeant Chaney assumed command, fell back, and sent word to Col. McCrillis. The remaining companies, now under Capt. Drummond, arrived with a howitzer to bombard the rebel position. Despite intense shelling, darkness forced a retreat.

Lt. William A. Heacock, age 23, was the first member of the 4th Iowa Cavalry to be killed in action. His loss demoralized the unit.

A Daring Escape and a Marked Man

We also find something interesting according to the records of the Gratiot (GRASH-it) Street Military Prison, operated in St. Louis, Missouri, by the Union Army:

A few minutes after the killing of Lt. Heacock, a local man named Capt. Jesse Mooney, C.S.A., was identified and spotted performing a daring feat, leaping onto his horse and safely swimming across the swollen river.

Since this amazing exploit was recorded, it would nearly cost Mooney his life in the future. To the Union officers, it made him complicit in the murder of Lt. Heacock. In time, however, Capt. Mooney would offer a very different account of both his death-defying escape and the man who pulled the trigger.

White River Skirmishes in April of 1862:

- Salt Peter/Nitre Cave, White River – April 18 (Companies G and K)

- Talbot’s Farm, White River – April 19 (Companies E, F, G, and K)

We would like to thank our sponsor, Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company, for their steadfast support of Retracing Our Roots. This is what true local programming looks like, where shared stories knit a community together. We couldn’t keep history alive without the heart and help of folks like Rapp’s. Next time you find yourself in Mountain Home, stop in at Rapp’s Barren Brewing. Shake the hand of Russell Tucker and his top-notch team and let them know you appreciate their part in preserving Ozarks’ history, one story at a time.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn. — Retracing Our Roots

Got a piece of history you would like to hear uncovered?

Drop us a line; we’re all ears.