ROR Question and Answers: from Prairies to Pioneers

Welcome to another episode of Retracing Our Roots with Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson. This week we took a batch of your questions, and boy did they arrange from the Ozark oddities to the battles in the ballot box.

First of all, we will delve into Ozark Cryptids. We will be focusing on those beasts creeping around from Ozark legend and sneaking through our prairies and hollers.

Cryptids in the Ozarks:

The Ozark Howler

Long ago, when the Ozark Mountains were still wild and untamed, whispers began of a creature

that prowled the moonlit hills. They called it the Ozark Howler, a shadow in the timberline with heavy black fur, eyes that burned like red coals and horns curling from its brow. Some say Daniel Boone himself first crossed its path deep into the Missouri woods, where he fired upon a black, snarling beast that vanished into the night. Legends tell he later warned settlers of its terrible cry, a howl so mournful it sent even seasoned hunters running for their cabins before dusk.

For over 200 years, Ozarkers have claimed to hear that same unearthly wail echoing through the

Ozark hills and hollers. In 2015, a traveler camping at Devil’s Den said he caught the creature in

a photograph; it had black fur, broad nose, horns like a deer’s, moving swift as a cat through the

trees. The pictures made their way to the newspapers, stirring excitement and fear in equal

measure. Yet, when the experts looked, they said it was no monster at all, just a trick of light or

clever editing. Still, the story spread as quickly as the howl itself, turning skepticism into shivers.

Even today, the Ozark Howler lives in the hush between the trees. Some swear it’s no more than

a mountain lion, others that it’s a spirit of the old frontier, bound to the mist and moss. On quiet

nights, when the forests breathe heavy and the wind curls through the hollows, folks say you can

still hear it. Some folks say it has a long, rolling cry of something wild and watching. And those

who’ve heard it never quite forget the sound.

Here’s a 2015 article from Wes Johnson of the Springfield Newsleader on the Ozark Howler. He

has a few pictures posted. Johnson: Do you believe in the Ozark Howler?

Ozark Bigfoot/Sasquatch: The Blue Man

The Blue Man, also called the Ozark Sasquatch, first appeared along Spring Creek in Missouri

around 1865, where famed hunter and trapper “Blue Sol” Collins tracked unusually large

footprints and stumbled on a gigantic, hair-covered creature hurling boulders from the hillside.

Armed only with a club and clothed in animal skins, the Blue Man became the terror of scattered

farmsteads, striking and disappearing for years at a time.

Farmers in remote hollows lost sheep, calves, and hogs, finding only clean-picked bones and

glimpses of a wild figure weaving through the timber. While brave search parties formed to capture him, the creature always managed to slip away, appearing every decade or so, and

growing frailer as the years went by.

Speculation about the Blue Man’s origins ranges from wild animal to wandering spirit, even to

rumors of a lost lineage linked to French, Spanish, and Native American roots in the Ozarks. By

the twentieth century, sightings dwindled but tales of missing livestock and eerie encounters

persisted, further cementing Bigfoot, and especially the Blue Man, as a permanent part of the

Ozark folklore landscape.

1865: The initial encounter with strange tracks and the first sighting by “Blue Sol” Collins along

Spring Creek, Missouri.

1865-1881: Over the sixteen years following the original sighting, the Blue Man was reportedly

seen multiple times, each appearance marked by new livestock losses and renewed efforts by

locals to capture him.

20th Century: Stories and reports of Blue Man-style creatures persisted into the 1911 and 1915,

particularly in local folklore throughout rural Missouri.

“Whitey,” the White River Monster

1915 – The Civil War Folklore (Unconfirmed)

Some old-timers whisper that the creature has haunted the White River since the 1860s, overturning Union transports during the war. No official documentation.

First Whispered Sightings

The legend of Whitey starts quietly. Folks fishing on the banks of the White River near Newport (Jackson County) report strange disturbances and shadowy shapes beneath the surface. No formal reports, just local mumblings. But the seed is planted, and something lurks beneath.

July 1, 1937 – Bramlett Bateman’s Witness Account

Dee and Sylvia Wyatt, a sharecropping couple on the river, were the first to spot Whitey. It had a

massive shape and thrashing around like a drowning horse in the middle of the White River.

They kept the sighting to themselves at first, fearing the laughter of neighbors. But when the wild

commotion persisted for days, they finally reported it to their landlord, Bramlett Bateman, a

well-known planter from a prominent family.

Once Bateman himself saw the creature churning

in a river eddy near his land, he rushed to Newport with a description that stopped folks in their

tracks: “as big as a boxcar and slick as a slimy elephant without any legs.” Others soon came

forward too, a dozen witnesses altogether, including a county deputy.

Bateman, being a practical man of the land, briefly considered the most Arkansas solution

imaginable: dynamite. After all, farms don’t plow themselves, and whatever was out there had

the potential to scare off labor or worse. Cooler heads and river regulations prevailed when

authorities told him no. The creature, for now, would have to roam free.

Summer 1937 – Monster Mania Begins

Fishermen notice a decline in catches. Sightings roll in, and Bateman’s story triggers national attention. Spectators bring cameras, rifles, and even a machine gun to help bag themselves a legend. A group builds a giant rope net, only to abandon the plan when the money runs thin. A deep-sea diver is sent underwater, but no monster was sighted. Skepticism followed, even rumors of hoaxing, but over 100 reported sightings make this something more than fish tales.

Summer 1971 – Whitey Returns

After decades of quiet, the monster shows its back again. One witness says it’s “the size of a

boxcar” with what looks like a horn or bone protruding from its head. Others say it has a spiny

back, twenty feet long. Strange three-toed prints, 14 inches each, appear on Towhead Island.

Trees are bent. Brush is flattened. Something big did some strolling.

1973 – The Monster Gets Legal Protection

Senator Bob Harvey introduces Senate Resolution 23. The Arkansas’s from Old Grand Glaize to

Rosie. A first for American cryptozoology: an official sanctuary for a creature no one can quite

explain. It’s now illegal to harm “Whitey,” even if you find him.

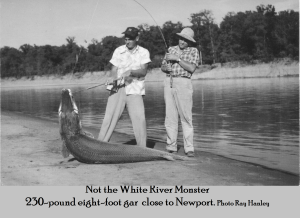

Theories and Ongoing Mystery

No modern sightings have been logged in decades, but the debates carry on. Some swear it’s an

elephant seal that wandered inland. Others propose a giant gar, sturgeon, or prehistoric holdover.

None of these fit every detail described by eyewitnesses. It remains Arkansas’s own aquatic

riddle, tucked snugly between folklore and history.

Arkansas Peace Society, the Yellar’ Rag Boys

Northern Arkansas in 1861 was not just a place where the Civil War tragically broke out, wasn’t just blue versus gray, but neighbor against neighbor. On May 6, 1861, Arkansas officially seceded from the Union to join the Confederate States of America on May 18, 1861; making it the ninth state to do so. The decision followed the attack on Fort Sumter and President Lincoln’s subsequent call for 75,000 troops, which shifted public opinion and the vote within the state’s secession convention.

The vote in the convention was overwhelming, but out in the upland counties, places like Van Buren, Izard, Searcy, Carroll, Fulton, and Marion, folks weren’t cheering as those in Southern Arkansas. Slavery wasn’t king here. These were hardscrabble farmers, Clod Busters, many descended from Tennessee and North Carolina stock, scratching out a living in the mountains

without plantations or enslaved labor. When the call went out for Confederate volunteers, a lot of them wanted nothing to do with fighting for the rich lowlanders and their “peculiar institution.”

The men stared backwoods meetings, they formed what became known as the Arkansas Peace Society. Sometimes called the Home “The society intended to protect itself at home... Left to itself in peaceful dissent, the brotherhood probably would have been merely a Unionist island of passive resistance.”

The Peace Society operated like the secret societies of the era: constitutions, oaths of loyalty, passwords, secret signs. One chilling symbol? A yellow rag or ribbon tied outside a home. It was a quiet signal of unity against the war. To angry Confederates, that earned them the mocking nickname “Yellar Rag Boys.”

Membership estimates increased as their secrets didn’t stay buried in wartime. By late 1861, rumors spread. Local vigilante committees, “citizens’ guards,” started rooting out the “traitors,” and they sprang into action. Izard County kicked it off, jailing 47 suspects.

Then, Colonel Samuel Leslie in Searcy County filled the courthouse in Burrowville (that’s Marshall today) with more. In December, Leslie chained 78 men together and marched them six grueling days south to Little Rock. It was a human chain gang of “disloyal” Arkansans.

Earlier, 27 from Van Buren County had arrived in the capital, and Governor Henry Rector was stumped. He wrote to Jefferson Davis, then to Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin, basically asking, “What do I do with these guys?” No clear reply came back.

By December 20, over a hundred prisoners faced the governor. The choice? Stand trial for treason... or enlist in the Confederate army to “wipe out the foul stain” of your resistance. Only 15 brave (or foolhardy) souls picked trial. Most took the uniform under duress. Forced into regiments, many of these men deserted at rates that horrified their officers. Some made it north to Union lines in Missouri.

For example, John Morris from Searcy County, of those chained marchers ended up at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. His captain barked to the troops: “If they try to get to the Federals, shoot them; if they fall back, shoot them; if they try to run, shoot them.” Morris survived, got furloughed, slipped home, then hightailed it to Springfield, Missouri, where he joined the First Arkansas Union Cavalry, fighting for the side he believed in all along. Others, like Paris G. Strickland, did the same: coerced Confederate service, then desertion to genuine Union regiments.

The Peace Society was crushed by early 1862. Arrests, forced enlistments, and fear did the job. After that, Northern Arkansas became a hotbed of guerrilla warfare. We had Jayhawkers raiding for the Union, Bushwhackers for the Confederacy.

In the end, roughly 90% of Arkansas’ Union soldiers, came from these very northern counties. More Union troops from Arkansas than from any Confederate state except Tennessee.

Great Ozark Resource to Research

What are some of the best references to Ozark Pioneers & life most area not aware of?

This question often comes in. Although there’s a lot for great Ozark material to draw from, I would like to highlight a source that is often overlooked.

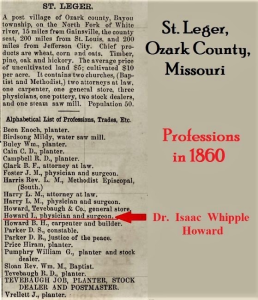

Isaac Howard’s Diary 1854 – 1858 in St. Leger, Missouri.

St. Leger was the second-oldest post office in Ozark County. Edgar St. Ledger Houth was the first postmaster in 1848. Much of what we know about St Ledger comes from Isaac Howard’s diary which he kept from 1854–58.

The diary was found in the trash after an estate auction several years ago. The diary describes what life was like living in Ozark County in the 1850s at or near St. Ledger (renamed Udall) near “The Bend” in what was the Big North Fork of the White River. It begins in 1854 and ends in 1858. Among other things, Howard also makes reference to the slaves owned by his neighbor, Job Teverbaugh.

Howard was obviously a man of many talents. He and his neighbors traded work and helped each other build homes and barns and raise crops. In addition, Howard was asked to write letters for his neighbors, make coffins for them, repair their shoes and even to bleed them.

The Ozarks Genealogical Society gave permission to The Old Mill Run to print selected excerpts from the article "The Diary of Isaac Howard, 1854-1858 (Ozark Co.)" edited by Mary Ellen Gifford, printed in the quarterly, Ozar'kin,Volume XVI, pgs 21-26, 67-71, 113-117, 167-169.(1994) by the Ozarks Genealogical Society.

Here’s a few excerpts of Isaac Howard’s diary in 1854:

Jan 2d 1854 Weather warm and dry. Made a coffin for a child of A. Blackburn’s.

Friday 6th Still very cold, laid foundation of kitchen and moved our house. Night McBrowning staying all night. A welcomed guest. Some good singing after supper.

7th Some snow fell last night and thinking it would be a fine time to find a deer. I hunted all day. killed 1 deer brought home hind quarters of the same. find myself very tired tonight and find myself in possession of dear [deer] meat.

8th now [snow] melted some. S. Russel came and stayed all night

Feb. 21st Still very cold. Turners wife badly burned last night by her clothes taking fire. Raised houses today. A good turnout of hands got done early.

24th Mrs. Monks died yesterday A little warmer today commenced making coffin this evening got it nearly done before bedtime.

April 20th, I have been hunting today but killed nothing. Perry Martin got whipped today for talking to much about other people’s business. Mr. Hubbard thumped him decently.

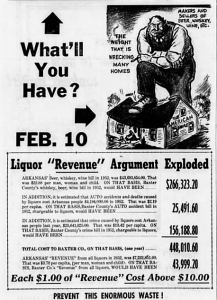

The Liquor Wars in Baxter County: Going from Wet to Dry to Wet

In a taut and spirited battle between Wet and Dry forces, Baxter County once again chose the path of prohibition. The special election held on February 9, 1954. The battle ended with a decisive victory for the Dry side, preserving the county’s long-standing ban on alcohol sales.

Over the years, Baxter County had migrated back and forth between Wet and Dry sentiment, never fully settling the matter. Local debates often wandered north across the state line, where Ozark County, Missouri, already wet, became the favorite cautionary tale. If Baxter ever legalized liquor, critics warned, it might “end up looking like Ozark County,” a comparison usually delivered with the sort of side-eye glare.

Unofficial returns last night showed 1,037 votes for legalizing liquor and 1,647 against it. Two small precincts remained unreported when the tabulation stopped, but with only about fifty ballots outstanding, officials noted that the final result would not change. A total of 2,684 votes were cast across the county. It was a sizeable turnout for a single-issue election.

This was the county’s first local-option contest since 1951, when the effort to legalize alcohol also failed, that time by a margin of 359 votes. Baxter County originally went dry in 1945, and every attempt since then to reverse the decision had fallen short.

When the dust settled, the message from voters was clear: Baxter County would remain dry, at least for a while longer. The debate, as always, reflected the religious cultural tension woven through the Ozarks.

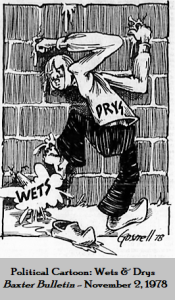

1978 - The Tide has Changed

In the November 1978 general election, the tides finally turned for Baxter County. In what became the heaviest voter turnout in the county’s history, local electors reversed more than three decades of prohibition and voted to move Baxter County from “dry” to “wet.” The change would become effective sixty days after Election Day.

More than 12,000 voters streamed into polling places from morning until closing time, a turnout amounting to 73 percent of all registered voters. The ballot question regarding the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquor is widely credited for driving the remarkable participation. When the votes were counted, the wet forces prevailed by a narrow margin of 184 votes. The tally stood at 6,175 in favor of legalizing liquor sales and 5,991 opposed.

The liquor question wasn’t the only hotly contested issue. Democrat Joe Edmonds captured a resounding victory in the three-way race for Baxter County sheriff. Edmonds, age 29 and a former State Trooper, was the son of Sheriff Emmet Edmonds, who had been slain in 1968 by an escaping prisoner. In the 1978 race, Joe Edmonds received 5,453 votes, 43 percent of all ballots cast, placing him well ahead of his opponents.

The defining feature of the day remained the countywide decision on alcohol, a vote that reshaped Baxter County’s legal landscape and marked one of the most consequential elections in its modern history.

𝐓𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐤𝐬, 𝐑𝐚𝐩𝐩’𝐬!

A special thank you to Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company for their sponsorship of 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨. Their continued partnership helps us share the real stories of the Ozarks, the kind you don’t always find in textbooks, but hear heart-to-heart across backroads and kitchen tables.

It’s thanks to local supporters like Rapp’s that the voices of our past still echo through these hills.

The next time you’re in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and the whole crew. Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company is helping us pour heart back into our local history.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨