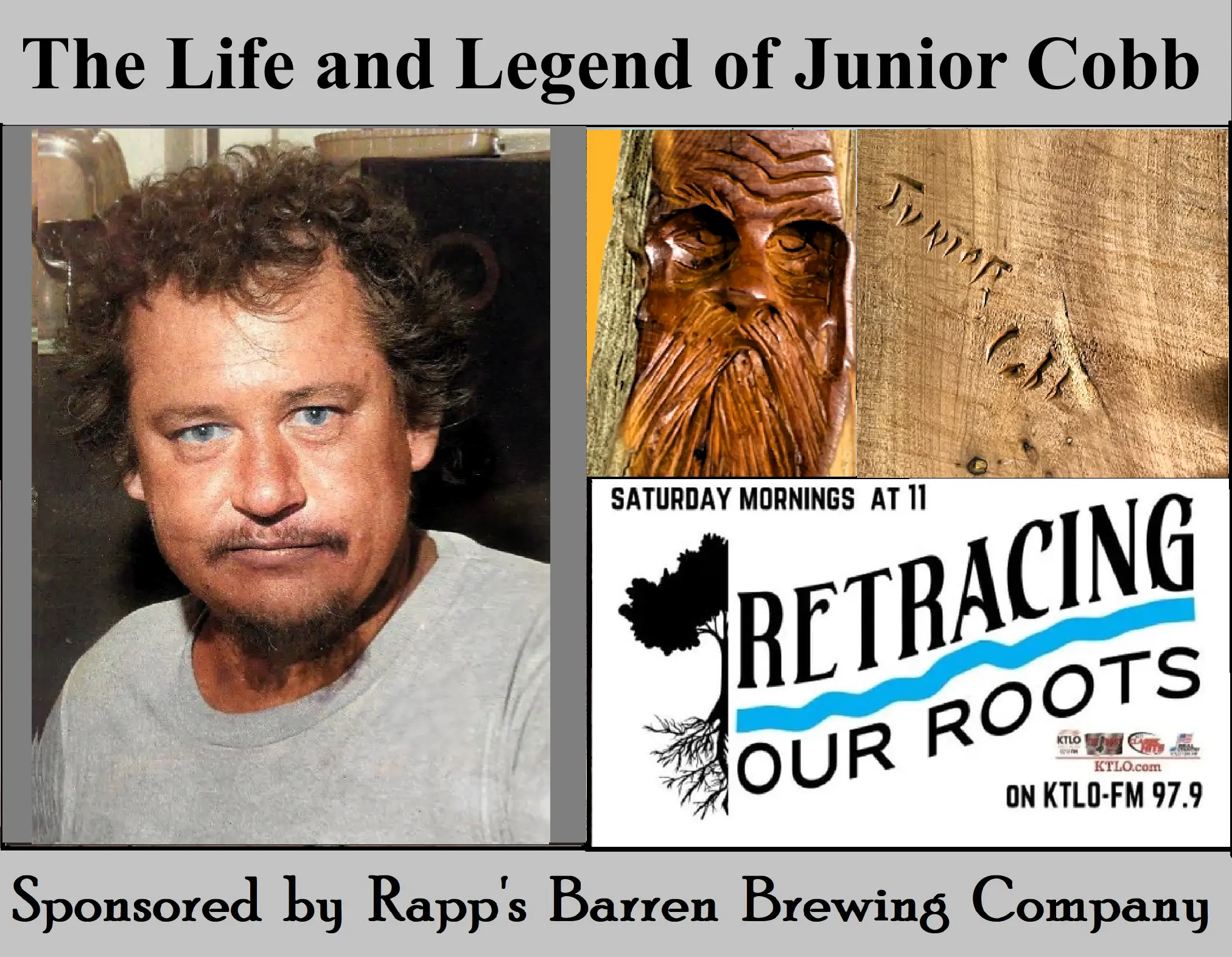

ROR: The Life and Legend of Junior Cobb

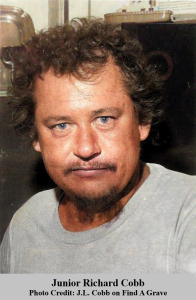

Welcome to Retracing Our Roots with Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson. Each week, we uncover the stories and characters that shaped the Ozarks, bringing history to life in ways both familiar and surprising. This week, we turn our attention to the life and legend of Junior Cobb. Mr. Cobb was a folk artist, storyteller, and unforgettable Ozark personality whose wit, carvings, and colorful presence left a mark far beyond the hills he called home.

1941 – Early Years

Junior Richard Cobb was born on March 24, 194, in Polk Sothern (sp), Arkansas. Most likely, it was near the Polk Southard Mine, an old manganese mine in Independence County, near Cushman, Arkansas. Junior was the son of Elmer and Ruby (Acklin) Cobb. Junior grew up along the White River before Bull Shoals Dam transformed the valley. His father, Elmer, operated a ferry across the river, guiding travelers between Shipps Ferry and Big Flat.

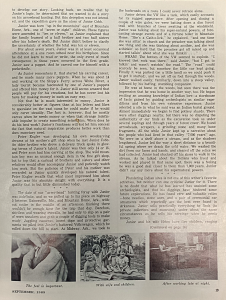

At the age of six, Junior saw someone with a puppet and decided to make one of his own. Using a pocketknife, he carved his first puppet from wood. Junior’s first puppet was a Howdy Doody hand puppet. His sister Virginia May later recalled how they would climb onto the chicken house roof to work together: “Junior would carve them, and I would make their clothes and use corn silk for their hair.” Junior joined the arms and legs with cotter pins.

Junior and Virginia May had once sold such creations for five dollars by the ferry their father, Elmer Cobb, piloted. Elmer had been both a river guide and the pilot of Shipps Ferry, which carried people across the White River to Big Flat well into the 1970s. From then on, woodcarving became a part of Junior’s life.

1940s & 50s – Youth in the Ozarks

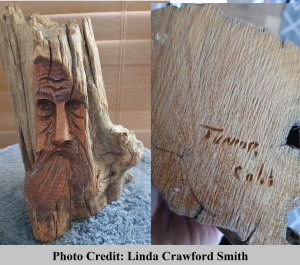

Junior spent his youth roaming the woods, bowhunting, and searching for arrowheads. He had little interest in reading or writing. Though he could sign his name or initials, “JRC,” he never learned the alphabet. He often joked, “I can’t read, but I can read Indian writin’,” explaining that he interpreted the hieroglyphics carved into Ozark cave walls.

Some said he looked like the old Anglo-Saxon pioneers who settled in the hills, while others whispered that he carried Cherokee ancestry. Local lore claimed his grandmother even had supernatural powers, which may have deepened Junior’s love of the wild places of the Ozarks.

On August 24, 1961, Junior married Helen Duncan in Midway, Arkansas.

1963 – TV Guide Feature & Rising Fame

At just 22 years old, Junior Cobb was profiled in TV Guide as a “real hillbilly” reviewer of the hit show The Beverly Hillbillies. Junior had never even seen the show until then. The nearest television was four miles away, and since he couldn’t read, he hadn’t followed any of the publicity about the Clampetts.

The article captured his natural humor, rustic wisdom, and knack for plainspoken truth. Junior compared Granny Clampett to his own grandmother, laughed at the idea of her moonshining, and said Jed Clampett reminded him of how “hill folks is like that sometimes, good at lettin’ on.” He whittled a figurine as he gave the interview, noting that his carvings brought in about $85 a month.

He liked Granny best, thought Jethro wasn’t too funny, and judged Elly May as simply “purty.” His wife Helen, who had married Junior at 16, agreed the show was entertaining, saying she enjoyed it more than other television comedies she’d seen while working in Midway.

For Junior, only two details spoil the show’s complete believability: the Clampetts’ 1921 Oldsmobile and the sponsor’s closing commercial.

“I don’t mean to say nothin’ against old cars,” explains the Arkansan, who has yet to own one of any kind. “Hereabouts they’s a good many like ther’n, but they just set in somebody’s yard, because they won’t pull the hills no more. Like the five miles from here to the hard road. An’ they’s bound to be a good many more hills from here to Californy.”

As for the commercial that bothered him, Junior says, “It just don’t seem right for Jad to light up a cigaret like he did. Seems as how it’d be better if he had a rolled-up one.”

When asked if he would move to Beverly Hills if he struck oil like the Clampetts, Junior admitted he might, but he added with characteristic honesty, “I know one thing certain. If it was me out there, I wouldn’t be lettin’ people take picsures of me for television, like they do the Clampetts—I’m smart enough to know I cain’t be as funny as they are!”

Mid-1960s – The White House Visit

In the mid-1960s, Arkansas Governor Winthrop Rockefeller invited Junior to Washington, D.C. There, he visited the White House and met President Lyndon B. Johnson. A legend later spread that he carved his name into a presidential desk. Both his nephew and his brother, W. A. Cobb, said Junior told the story himself, but W. A. suspected it was just one of his tall tales. Junior typically signed his works with his initials “JRC,” not his full name, and no evidence of the carving has ever surfaced. Still, the story became part of his colorful folklore.

1969

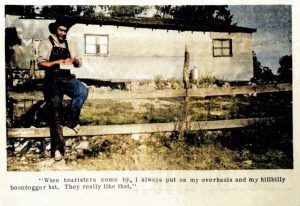

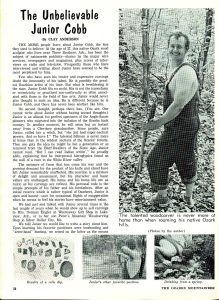

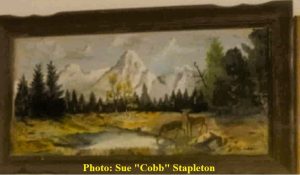

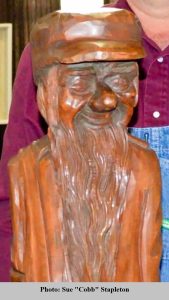

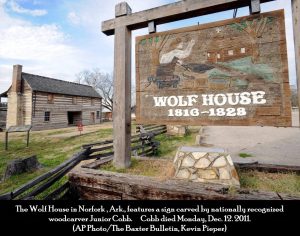

By his late twenties, Cobb’s artistry was gaining attention. In 1969, The Ozarks Mountaineer told his story, and before long, newspapers, wire services, magazines, and radio and television stations across the country were featuring his work. Cobb’s carvings of ducks, woodland birds, and “hillfolk” figures in floppy hats and overalls displayed both humor and craftsmanship.

Junior began working with Peter Engler, a fellow carver with a gallery in Branson, Missouri. The two worked together at Silver Dollar City, where Junior’s homespun wit made him a favorite during promotional tours. Engler remembered, “He was so genuine and so real, but the disc jockeys in St. Louis and Kansas City didn’t know if he was putting them on.”

During this period, Cobb also sold carvings through Mrs. Norman Engler at Whereaway Gift Shop in Lakeview, Arkansas. His work began appearing in major collections and eventually examples of his carvings found their way to Europe, the White House, and the Smithsonian.

Each year, Junior turned out hundreds of finely crafted pieces—native birds, wooden Indians, hillbilly figures, and wall plaques. His work earned him the respect of fellow Ozark artists and the admiration of tourists, many of whom clamored for an “Original Cobb.”

Junior once chuckled recalling, “A Chicargo tourister gave me a $30 tip last week. I charged him $20 for a cedar quail, and he hollered I warn’t gettin’ enough, so he handed me a $50 bill.”

1970s–1980s – A Free Spirit

In 1970, Junior went again to Washington D.C. to the Smithsonian’s, Festival of American Folklife. His talent was highlighted along with fellow woodcarver, Jimmy Nelson.

Junior was also the subject in a chapter of National Geographic’s book, Mountain People.

Despite growing fame, Junior’s life remained simple and rustic. He had no phone and was often hard to find. He would vanish into the woods for days at a time, hunting or digging for artifacts, only to reappear when he needed money. “He would come and find us, generally when he wanted to sell a few carvings,” Engler said. His brother W. A. explained, “He wouldn’t even carve until his wife got after him. He’d have probably been rich if he’d have hung on to his money, but money didn’t mean nothin’ to him.”

His carefree spirit often clashed with responsibility. Once, a collector arranged for him to carve a piece by the next day. When asked later if he had delivered, Junior replied with a grin, “No, I decided I wanted to go swimmin’.”

Junior Cobb also made it on to the Glen Campbell Show as he presented a carved bust of Arkansan, Glen Campbell.

1995 – Reflections and Craft

In 1995, Junior was still carving daily, using nothing more than an old hickory paring knife that cost $1.98. His carvings ranged from life-size human figures to tiny hummingbirds and even requested scenic pieces. The tools remained modest, but the range and imagination of his work proved the depth of his genius.

2000s – Decline in Health

Late in life, Junior suffered a stroke that required quadruple bypass heart surgery. The stroke left him blind and partially paralyzed, ending his carving career. Poverty and ill health weighed heavily on him, and his brother W. A. admitted, “It was probably a blessing he passed, he was hurting towards the end there.”

2001 – Death and Legacy

Junior Cobb died on December 12, 2011, at the age of 70 at Gassville Nursing Center. He left behind a wife and five children. Visitation was held at Roller Funeral Home in Mountain Home, and he was buried at Three Brothers Cemetery.

For his friends and admirers, his legacy was far richer as he lived out his Ozark heritage. Peter Engler said, “I can close my eyes and see him. Completely a free spirit.”

Junior Cobb is looked upon as both a master artist, a folk legend, and storyteller of the Ozarks. His work carried the spirit of the hills into national museums, even as his stories kept alive the mystery and mischief of a man who never stopped living on his own terms.

What some in our community say about Junior Cobb:

Les Kitchell:

My Dad knew him very well, they went together many times arrowhead hunting & explored several Caves together!

Paul Worman:

My grandparents knew him very well, they used to sell his carvings at the dock when they owned Cranfield Marina!

Lyn Sullivan:

I attended elementary school at Midway, and I recall him bringing a marionette he had carved to school to show us. This was probably 1960ish. His carvings were sold at Button Mosaics gift shop in Lakeview for years before he gained a measure of fame

Erica Harris:

In the late 80s and early 90s my parents ran a store in Gassville between Sanders Car lot and the tow place, they sold Juniors carving there. I still have a couple small ones. I loved Ol’ Junior. He would tell me all kinds of crazy stories especially ones about acid rain and giant tornaders. He was a fun guy.

Annette Shockey:

Junior Cobb was my uncle. He was an amazing man that didn’t care about money or material things. He would always help anyone. He was one of a kind.

James Crawford:

I sold Junior probably the first and only new car he had ever owned, a 1979 AMC Spirit from Hemmert's Auto Mart.

Junior used to set up on the courthouse lawn and carve. He had carved & painted some ducks & a man asked Junior, "How do make them look so real? Junior said, “Ya take ya a piece a wood and cut off what don't look like a duck."

Sarah McCabe Collection:

On Junior Cobb’s carvings, there is a special Sarah McCabe Collection. The Collection is noted by Junior’s name, Date, and the Number 1 is Circled.

Special Thanks!

Special thanks to Sue “Cobb” Stapelton, Junior’s oldest daughter, and her husband, Kenny, for their assistance and hospitality in researching this show! Sue also told us that Junior Cobb appeared in an episode of the Beverly Hillbillies.

Thank you, Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company!

A big thank you to our friends at Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company, and congratulations on your 8 year Anniversary. Their ongoing support is what helps Retracing Our Roots echo through the hills with the true stories of the Ozarks, stories you will not find in the average history book. It is partnerships like theirs that keep our heritage alive, one story at a time.

Next time you are in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and his incredible team. They are helping preserve local history with heart and hometown pride.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

Retracing Our Roots