ROR: 𝐖𝐡𝐢𝐭𝐞 𝐑𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐄𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 & 𝐄𝐱𝐩𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬

Welcome to 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨 on a special historical journey down the White River with Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson. The decks are crowded, the boilers are hot, and the past is about to surge back to life. This week we'll travel through 𝐖𝐡𝐢𝐭𝐞 𝐑𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐄𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 & 𝐄𝐱𝐩𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 and discover the thrill and danger of steamboat transportation on the White River. So, tighten your lines and step aboard as our voyage into the river’s explosive, along with its exciting excursions of the past.

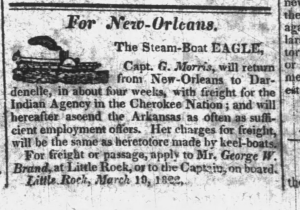

As we focus on steamboats specifically this week, we will take a look at the first steamboat expedition in Arkansas, the Eagle.

New Era for the Arkansas & River Travel

The morning of March 16, 1822, in Little Rock was like any other, filled with the sounds of axes on timber and the slow, muddy flow of the Arkansas River. Then, a sound shattered the familiar quiet on the river valley. It was not a clap of thunder or a dinner bell call to supper, but the deep, resonant blast of a steam whistle which was more than a formal announcement of its arrival. It was the beginning of a transportation revolution.

Heads turned and work stopped. The citizens of the small frontier settlement of Little Rock rushed to the riverbank, their surprise as intense as the spring air. There, rounding the bend, was a vision of modern marvel: the steamboat Eagle. The boat’s stack was belched smoke, and its paddlewheel churning the sediment laden water into a froth.

Captain Morris stood at the helm, the architect of this miracle. His vessel had made the run from Arkansas Post in just 51 hours. It was a journey that would have taken a keelboat…weeks of back-breaking labor. In 17 days from the bustling wharves of New Orleans, he had brought the future to Little Rock’s doorstep.

The Eagle did not anchor long on the riverbank, stopping only for an hour. It was bound for Dwight, the Cherokee Missionary establishment far upriver, a symbol of the changing world in more ways than one. As it continued its voyage, the sight of its retreating stern left the townsfolk abuzz. The Arkansas Gazette proclaimed it, and they felt it in their bones: this was the first steam that had ever ascended the Arkansas River to their little vicinity. It was an act of pure enterprise, and it reflected immense credit on the bold captain who dared to accomplish this task.

The hope Captain Morris left on his departure upstream was as tangible as the boat itself. He reported encountering “no great difficulty,” even with the river at a very low level. Morris assured everyone that at a higher stage, the Arkansas River would be “as well adapted to steamboat navigation as any in the world.”

This was more than just a visit; it was the opening of a new and interesting era. For the farmers already increasing their industry, for the planters making their first efforts to raise cotton, the Eagle was a promise.

True to the captain’s word, the Eagle returned to Little Rock, having successfully discharged its freight for the Mission just twelve miles short of its final goal, turned back only by the shallowest of waters. It took on new cargo and turned its bow downstream, a promise to return in about four weeks with freight for the Indian Agency.

Among the passengers who had disembarked upstream was the Arkansas Territorial Governor, James Miller, himself, traveling to Fort Smith on business relating to the Cherokee and Osage Indians. His presence on the Eagle was a silent witness to the boat's significance. The future had not only arrived with a blast of its whistle; it was now carrying the business of the territory, shaping its destiny with every turn of its paddle wheel.

When word spread that the Eagle had pushed its way up the Arkansas River, folks along the White River broke into rejoicing. If a steamboat could conquer the snag-choked water of the Arkansas, then surely it could reach a further distance up the White, a river far less hindered and far more inviting to steam and commerce.

Steamboat Arrives, Almost: Destination Forsyth, Missouri.

As the years rolled on and steamboat technology advanced, the horrific steamboat tragedies did not stop, and the White River had its fair share of them.

In March 1851, the Missouri legislature moved to improve the White River. Their appropriation was paired with private capital from prominent Springfield citizens eager to open a river trade route to their city. That summer, a steamboat attempted to reach Forsyth but was forced to stop roughly two miles below the Arkansas line. By that time, work had begun to deepen the channel at the shoals. Records show that in 1851 “Hack” Snapp was hired to cut a new channel through the shoals near the mouth of Elbow Creek.

“The next spring, the steamboat Yaw Haw Ganey, actually “Yohoganey,” approached the new channel,” writes Ozark Historian Elmo Ingenthron. “All day long the steamboat labored in the channel trying to pass over the shoal. A number of passengers came ashore to lighten the load and waited on the banks of the stream. Still, the Yaw Haw Ganey failed to make the shoal and was compelled to back downstream and unload 300 sacks of salt belonging to the merchants of Forsyth. The following day, she ascended the shoal and completed her trip. Jim and Tom Clarkston were employed to haul the salt by ox wagons overland to Forsyth.”

Aboard the Yohoganey was a young man named Albert Gatlin Cravens, a man who would go on to build a life and career on the White River that fixed his name in its history. His first arrival by water was only the beginning; before long, Cravens would become one of the river’s most familiar and enduring White River captains and figures.

The Fiery Loss of the Steamer Caroline, the "Belle of the White River"

The medium-sized Memphis packet, Caroline, was a sternwheeler with a wooden hull, built in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1853. She weighed 103 tons and measured 134 feet long by 24 feet wide, with a shallow 3.5-foot draft designed for rivers like the White. But on Sunday, March 5, 1854, this vessel, once known as the "Belle of the White River," met a catastrophic end.

The Caroline had ascended about twenty miles up the White River, hauling the U.S. Mail and freight, when at 2 o'clock in the afternoon, the wood pile near her boilers was discovered to be on fire. The pilot at the wheel, Mr. John R. Price, immediately steered for the shore, but the river was high and the banks were flooded. Before the boat could land, panic erupted. Some attempted to escape in the ship's yawl, but it was tragically overcrowded. The small boat sank instantly, drowning everyone aboard.

The flames, meanwhile, raced across the steamer. It was soon consumed down to the water's edge. There were many deck passengers on board, nearly all of whom were lost. The principal sufferers were the women and children, who were unable to make the desperate exertions required for survival.

The list of the lost was heartbreakingly long. It included the two pilots, John R. Price and James Creighton; Lewis Pollock, the assistant bar-keeper; and eight deck hands and firemen whose names the captain's report omitted. The tragedy erased entire families: the wife and child of J. Haskins; the four children of S. McMullen; Mrs. Haley and her three children; and John Horton, his wife, and their two children. In one of the most devastating blows, a widowed sister of a Mr. Wortham perished with all thirteen of her children.

James T. Lloyd, in his 1856 book Lloyds Steamboat Directory and Disasters on the Western Waters, recorded the profound shock that swept through Memphis when the steamer Memphis brought the news the following Monday. The Memphis Evening News wrote, "We cannot find language to express the feelings awakened in our bosom..."

Their report paid special tribute to Pilot John R. Price, who had only recently been married. "She who so lately was a joyous and happy bride, now is a bereaved widow," it noted, adding, "Poor Price! When last seen, he was at his post endeavoring to run the boat ashore in which he succeeded and lost his own life in the heroic attempt to save the lives of others."

The material losses were immense. A safe containing $5,000 [$190,000 today] sank into the river and was never recovered. Another passenger, Mr. Penn, lost $3,500 [$130,000 today]. In a final, macabre twist, the remains of Mr. Wilbanks, which were being transported for burial, also found a grave at the bottom of the White River, along with a package of money he had destined for his widow.

When the steamboat’s hull, burned through, finally broke in two, it sank in about 30 feet of water. The total loss was estimated at $150,000 [$5.9 million today]. Out of a large number of passengers, very few were saved. Of ten deck hands, only two escaped. The "Belle of the White River" was gone, her story remains a very somber and permanent scar on the memory of the river.

By October 1861, the "elegant and swift passenger steamer" had been renamed Eliza G. and was commanded by J. H. Quisenbury (or Quisenberry) of Batesville, Arkansas. Advertisements promoted its ability to transport freight to all landings along the White and Black Rivers. By February 1862, its route expanded to include the Little Red River, offering service to "Pocahontas, Jacksonport, Des Arc, and all landings" along these three waterways.

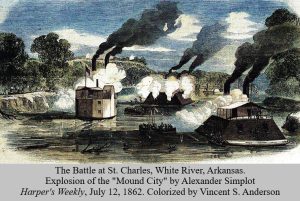

The Eliza G. soon began serving as a Confederate transport and was present at St. Charles in June when a Union fleet carrying supplies for Major General Samuel R. Curtis’s Army of the Southwest approached. Confederate engineer Captain A. M. Williams stated that, following orders from Major General Thomas C. Hindman, the steamboats Eliza G. and Mary Patterson were scuttled to block the river and prevent Union gunboats from passing. Captain Leary oversaw the scuttling, while the crew of the CSS Maurepas sank their gunboat to ensure the blockade.

The battle on the White River at St. Charles, Arkansas, on June 17, 1862, is recorded as one of the most tragic naval encounters of the Civil War.

During the engagement, a Confederate solid shot slammed into the ironclad USS Mound City, puncturing one of her steam drums. In what has often been called the deadliest single shot of the war, scalding steam filled the ship, killing or wounding all but about twenty-five of the roughly 175 men aboard.

The Eliza G., Mary Patterson, and the CSS Maurepas still sleep beneath the White River, their hulls entombed in its bed.

McBee / Yellville Landing

One significant steamboat landing on the upper White River is the McBee Steamboat Landing. The popular landing sat on the White River just upstream from Cotter, Arkansas, about a quarter-mile south of the present-day Highway 62 bridge between Baxter and Marion Counties and only eight-tenths of a mile above the railroad bridge. Often referred to as the Yellville Steamboat Landing, it served as a busy river port where important steamboats, keelboats, and flatboats loaded and delivered freight. Farmers growing small bales of cotton and tobacco relied on boats such as the Waverly, Home, Lady Boone, and Ozark Queen to move their goods to market.

Steamboat Ozark Queen

The Ozark Queen was a mainstay on the White River. She was a stern-wheel packet with a wooden hull, built at Batesville, Arkansas, in 1896. She measured 133 feet by 25.6 feet, carried 9½ x 3-foot engines, and had one boiler measuring 44 inches by 20 feet.

In 1896 she entered service under Capt. C. B. Woodbury for White River trade. By May 1903 she was in the Batesville–McBees (near Cotter) run under Capt. William Shipp with John Shipp as pilot, the same family name that survives at Shipps Ferry.

In December 1904 the Ozark Queen was condemned at Memphis and sold to Capt. M. F. Bradford. She was rebuilt at Madisonville, Louisiana, in 1906 and renamed the Houma, owned by the Bradford Transportation Company. Under that name she ran out of New Orleans into the Lower Terrebonne country, to the sugar refinery at Houma, and up Bayou Lafourche to Lafourche Crossing. By 1909 she was under Capt. T. W. Cook with A. Rodriquez as clerk.

Ironically, she escaped a severe windstorm at New Orleans, only to be destroyed by fire a short time later, in September 1926.

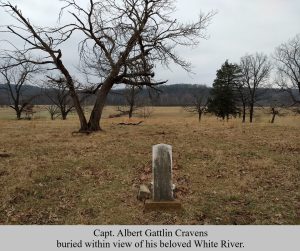

Albert Gallatin Cravens

Albert Gallatin Cravens was one of the White and Buffalo Rivers’ most daring and colorful steamboat pilots. In 1896 he built the tiny packet steamer 𝙏. 𝙀. 𝙈𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣 and famously piloted it several miles up the Buffalo River on Easter Sunday, proving that shallow water couldn’t hold him back.

Cravens had earlier captained the 1869 keelboat 𝙀𝙡𝙞𝙯𝙖 𝙅𝙖𝙣𝙚, and later commanded the steamers 𝘼𝙧𝙜𝙤𝙨, 𝙇𝙖𝙙𝙮 𝘽𝙤𝙤𝙣𝙚, 𝙍𝙖𝙣𝙙𝙡𝙚, and 𝙈𝙮𝙧𝙩𝙡𝙚. He once narrowly escaped death after being sucked beneath a larger steamer, only to resurface clinging to a willow branch.

Albert Gallatin Cravens was one of the White and Buffalo Rivers’ most daring and colorful steamboat pilots. In 1896 he built the tiny packet steamer 𝙏. 𝙀. 𝙈𝙤𝙧𝙧𝙞𝙨𝙤𝙣 and famously piloted it several miles up the Buffalo River on Easter Sunday, proving that shallow water couldn’t hold him back. Earlier he had captained the 1869 keelboat 𝙀𝙡𝙞𝙯𝙖 𝙅𝙖𝙣𝙚, and later commanded the steamers 𝘼𝙧𝙜𝙤𝙨, 𝙇𝙖𝙙𝙮 𝘽𝙤𝙤𝙣𝙚, 𝙍𝙖𝙣𝙙𝙡𝙚, and 𝙈𝙮𝙧𝙩𝙡𝙚. He once narrowly escaped death after being sucked beneath a larger steamer, only to resurface clinging to a willow branch.

Cravens also built a name for hospitality along the White. An 1887 newspaper describes a picnic at Ervin’s schoolhouse in White River Township—swinging, dancing, courting, ice cream and lemonade stands, and a dinner furnished in part by “the better two-thirds” of T. J. Barb and A. G. Cravens. Cravens had caught and contributed a “fine mess” of fish the night before, cooked “to please the most fastidious epicure.”

A similar spirit appears in an 1890 account of a fishing party. “On last Saturday morning,” it records, “about a dozen young people, on pleasure bent, left Yellville expecting to meet a similar party from Mountain Home at Denton’s Ferry.” They reached “the beautiful and romantic White River” about ten o’clock and found their Mountain Home friends waiting on the west bank. After introductions, the whole company crossed to the Baxter County side. Miss Lillie Brooks supplied hot coffee, while Misses Horton, Brooks, Casey, Livingston, Dyer, Truman, Layton, Hurst, and others arranged the dinner.

“About this time,” the writer adds, “an incident occurred that can best be explained by Miss Ada Layton and Miss Rose Brooks, who were in possession of Dr. Simpson’s cart. “The evening passed in boat riding, buggy and horseback riding, strolling, and gathering shells from the riverbank. and other amusements. Around six o’clock the party began to disperse. They shook hands and parted happily; the Mountain Home party accompanied the others to the riverbank, and when they were halfway across, hats and handkerchiefs were waved until both groups turned homeward feeling that they had spent a pleasant and happy day.”

On May 30, 1931, just two days shy of his 92nd birthday, Albert G. Cravens passed from this life. A portion of Capt. Cravens’ obituary succinctly sums up his life:

“Many years of his life were spent on the White River as captain of steamboats which plied between Newport and the Upper White River, and during those years no man knew the channel of the river better than he. He loved White River almost as much as he loved his life, therefore it was very fitting that after his soul had passed to its reward, that his mortal body should be conveyed up the White River railroad, along the winding banks of that beautiful stream, and laid to rest in the Barb Cemetery, which nestles almost at its brink, near the uppermost landing place where he had many times anchored his boat in the years of long ago, and there above high water mark, in a beautiful grove, near the Cravens' farm-his old home-where the breaking of the waves of this beautiful stream on its journey to the sea may be heard by the generations who follow him until time be no more.”

Capt. Albert Gattlin Cravens left behind not only a long life, but a river’s worth of stories that still run through Ozark memory.

𝐓𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐤𝐬, 𝐑𝐚𝐩𝐩’𝐬!

A special thank you to Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company for their sponsorship of 𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨. Their continued partnership helps us share the real stories of the Ozarks — the kind you don’t always find in textbooks, but hear heart-to-heart across backroads and kitchen tables. It’s thanks to local supporters like Rapp’s that the voices of our past still echo through these hills.

The next time you’re in downtown Mountain Home, stop by Rapp’s and thank Russell Tucker and the whole crew. Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company is helping us pour heart back into our local history.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨