Retracing Our Roots

Cartney, Arkansas – A History in Stone.

Welcome to another intriguing episode of this week’s Retracing Our Roots. Today Heather, Sammy, and Vincent drill down into the history of a town that no longer exists as it once did—Cartney, Arkansas. But before we venture into the history along the White River, let’s dig into our mailbag and hear from one of our listeners.

We received a message from Dr. Ray Stahl concerning one of our past episodes on poisoned whiskey used for medicinal purposes. Dr. Ray said:

I believe they could have died from drinking methanol (wood alcohol) rather than ethanol. Small amounts can kill. You can Google ‘methanol poisoning from improperly produced moonshine’ for details on how this can happen. I remember hearing about this while I lived in East Tennessee. (The hills were alive with stills!)

Lead poisoning from making moonshine in radiators also led to the development of Jake Leg, from damage to peripheral nerves. Also, the very high ethanol concentrations in moonshine can depress breathing, etc., leading to death. The moonshiners didn’t have a reliable way of testing the percent of alcohol produced. Whether it was methanol, high concentration ethanol, or some other contaminant—moonshine can be bad stuff.

Now, let’s step alongside a portion of the White River that was once a thriving community and railroad depot, and the village that still holds national significance in the stone masonry industry and history.

The community originated as Haney, Arkansas. When a post office was established, the U.S. government slightly changed the spelling to Hayney, though it was still pronounced the same. The little settlement was named after Sam Haney, the postmaster and general store owner.

Between 1892 and 1896, a geological survey was conducted in the area by a young college student named Herbert Hoover. In his survey, he discovered a strata of marble on the hillside suitable for lithography. This young man will become relevant again by the end of today’s episode.

Sam Haney lived quite an eventful life. In 1905, he was fined $100 for selling clandestine liquor, and in 1907 he was charged with disturbing the peace. But those youthful scrapes didn’t seem to follow him much further. After Sam was no longer postmaster, W.V. Hamrick emerged as a local merchant, known for a fine line of groceries, cigars, and tobaccos.

Sam began contracting with the Missouri Pacific Railroad, working to widen the grade between Cotter and Norfork. On the side, he gained a reputation for selling the best frying chickens at just 25 cents a pound. Life seemed good as Sam also operated a ferry between Hayney and Lone Rock, Arkansas. But disaster struck in 1915 when a massive flood washed away the businesses of both Hamrick and Haney. The Haney Hotel lost much of its structure, though the railroad depot fortunately sustained little damage.

Then came another blow. In September 1919, Sam’s ferry was dynamited, not once, but twice, even after repairs. Thinking things were getting a little too hot on the White River, Sam and his family slipped away to Oklahoma for about a year.

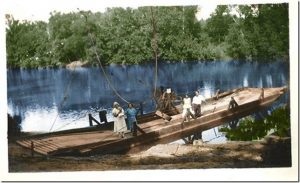

But the little town bounced back and rebranded itself as Cartney, hoping for brighter days ahead. Cartney became a gathering place for cedar logs harvested in the rugged Ozark hills. Large rafts floated downstream—from Cartney to Calico Rock, and then on to Batesville, Arkansas.

In the early 1920s, Cartney gained fame for having the prettiest station manager on the White River Division. Mrs. Stella Barton Beavers was cooking for a railroad work gang when she heard the Cartney station agent position would soon be open. She inquired if she could apply—and to her surprise, she got the job.

For $18 a month, plus commission on all ticket sales, Stella sold tickets, logged freight shipments, met all passenger & freight trains, carried the mail to and from the post office, and maintained three switch lights.

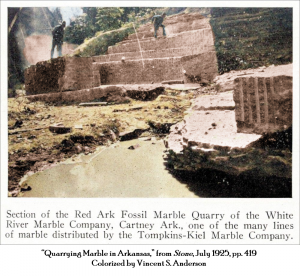

The nearby farm of Holywell Trimble and his father housed a large Arkansas “marble” mine. The mine was leased to a company that quarried the stone, shot it down the river bluff to the tracks, and shipped it to Carthage, Missouri, and Batesville, Arkansas. There were two quarries, one for gray marble and one for pink marble, also known as marble horn. Cartney stone was reportedly used in the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City.

Now, let’s settle a common myth: No, this marble was not used in the Washington Monument. That stone came from the Marble Falls area. However, tons of pink and gray stone still dot the hillsides along the White River.

According to the 1892 annual report from the State Geologist of Arkansas, St. Joe Marble is found in great quantities in the Leatherwood Mountains of southern Baxter County. The stone occurs in 4-to-6-foot-thick layers just a few feet beneath the surface.

Eventually, the quarry was purchased by Howard Wolford, who founded the White River Marble Company.

In late 1929, a special order came in for the White River Marble Company’s Arkansas Red Fossil, Baxter County’s famous pink stone. (In truth, the stone is not actual marble, but it is sedimentary stone with a rich matrix of small fossils.) This special stone was hauled off the hillside, slid down the mountain, and loaded onto the railroad. It was taken to Batesville to be cut, polished, and engraved.

That stone became President Abraham Lincoln’s cenotaph, or tombstone. The expansion of the Lincoln Mausoleum began in 1930 and was dedicated on June 17, 1931, with President Herbert Hoover presiding over the ceremony. Little did Hoover realize that, 35 years earlier, he had surveyed the very hillside that would yield the stone for Lincoln’s monument.

Today, President Lincoln is buried 30 inches behind his tombstone and 10 feet down, encased in concrete and steel, at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

In a time when monuments and history have been hotly debated, we can reflect on this truth: A Southern stone, from Baxter County, Arkansas, honors a Northern president, Abraham Lincoln.

Each year, thousands pass through Lincoln’s mausoleum, pausing in reverence before a piece of stone hewn from the hills of Baxter County, Arkansas. As they move quietly by, they reflect on the weight of the past, and hopefully, carry with them hopes for the future.

A warm and sincere thank you to Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company—steadfast supporters of Retracing Our Roots. This is what real, hometown storytelling looks like: where shared memories tie a community tighter than any ordinance ever could. Without the heart, heritage, and help of folks like Rapp’s, we couldn’t do what we do of reviving the past and passing it along, one story at a time.

Next time you're in Mountain Home, swing by Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company and thank Russell Tucker and his top-notch crew for championing local history that still matters.

Sip. Savor. Sojourn. — Retracing Our Roots

Got a piece of history or local legend you'd like to hear more about?

We're all ears! So, drop us a line, and we’ll dig it up.