𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙊𝙪𝙧 𝙍𝙤𝙤𝙩𝙨 #27

𝘿𝙚𝙖𝙩𝙝 𝙛𝙧𝙤𝙢 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙃𝙚𝙞𝙜𝙝𝙩𝙨 𝙤𝙛 𝘾𝙤𝙩𝙩𝙚𝙧

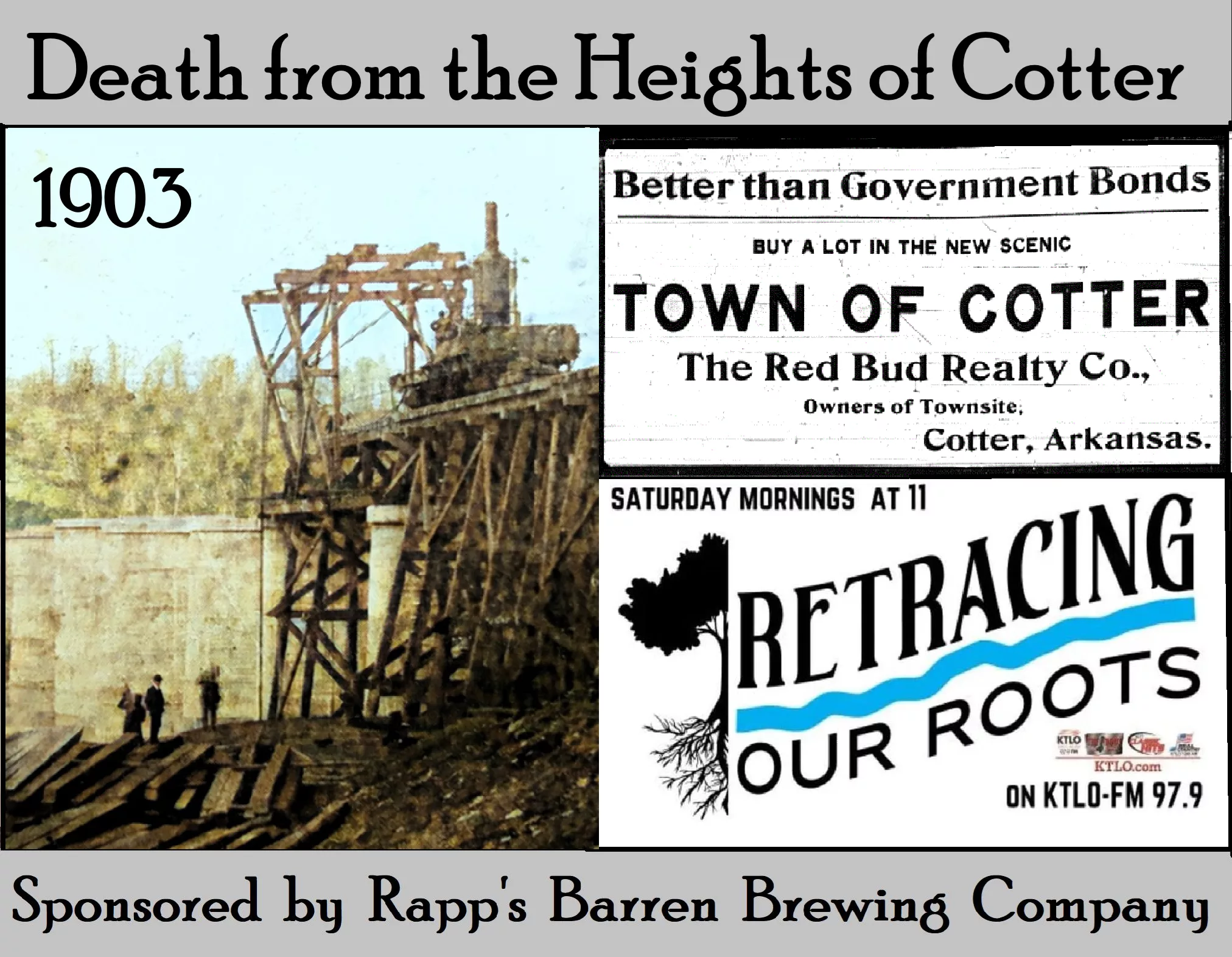

Join us today as Sammy Raycraft and Vincent Anderson discuss the high price of progress in Cotter, Arkansas, during the construction of the railroad bridge across the White River in 1903.

We focus on the story of Louis Collins from Ozark County, Missouri. Louis and his wife, Alice, soon began building a family. Over the years, finding employment to support his wife and their four children became a priority—not only for Louis but also for many men in the Ozarks. By 1901, news of the railroad building a thoroughfare along the White River gave hope to families seeking better opportunities for commerce and transportation. Additionally, men found work along the route, often bringing their families with them. One such place of promise was Cotter, Arkansas.

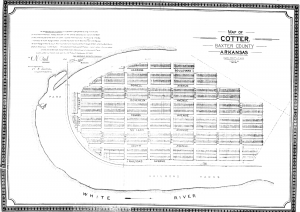

The newly formed Red Bud Estate Company devised a plan to establish Cotter as a railroad boomtown. Economic prosperity began to bloom in the White River region, and the company started selling lots along the river. Cotter quickly became a hub of growth and ingenuity. However, the influx of workers led to a housing shortage, forcing many men and their families to live in tents. Louis Collins and his family were among them, residing in a tent at the railroad camp. Within a year, Louis was able to provide a new house for his family in Cotter Arkansas.

Many locals found employment cutting railroad ties, flooding the White River with freshly hewn timber. Doctors, dentists, and all manner of businessmen and merchants soon had their sights set on the fledgling town. As the railroad progressed from Batesville and Calico Rock, Arkansas, another major project was underway: the construction of the railroad bridge across the White River at Cotter.

Louis worked as a signalman atop the high piers—a dangerous yet vital position. He had held this role for some time, earning the trust of the camp leadership. His responsibility was to signal the engineer to start or stop, and to raise or lower the concrete box used for the pier’s foundation.

On the morning of Friday, December 11, 1903, around 8 o'clock, Louis gave the signal to raise the box after a load of concrete had been deposited into the pier. The box shot upward with such force that it struck the carriage castings on the cable. The impact caused the rope holding the box in place to snap. The heavy box plummeted approximately 32 feet, striking Louis on the head and crushing his skull. His body then fell from the pier into the coffer dam below—a distance of 42 feet. During the fall, he hit a 2x6 beam on the framework, breaking and mangling the bones of his right hip and upper thigh. His body eventually lodged on another beam near the surface of the water in the coffer dam.

Louis was pulled from the water unconscious and taken to his nearby home. Three Cotter physicians and one from Mountain Home were summoned. Despite their efforts, including a surgical operation, Louis succumbed to his injuries at 2:30 that afternoon, having survived for over six hours after the accident.

His body was prepared for burial and transported the next day to Gainesville, Missouri, the home of his brother, J.W. Collins. The interment took place late Sunday evening at the Gainesville Cemetery. Louis was 31 years old, leaving behind his wife, Alice, and their four children.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, the community of Gainesville, Missouri, rallied around Alice and her children. John Harlin, president of the Bank of Gainesville, traveled to Cotter on a fact-finding mission. Upon his return, Harlin hired local Ozark County attorney, Gut T. Harrison, to pursue legal action regarding Louis’ death.

At this time, the outcome of the proceedings and whether the family received any compensation remains unknown. Although these details of the case are lost to history, the compassion and sense of community that emerged stitched the Ozark region even tighter together along the White River Valley.

We are incredibly thankful for Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company and their unwavering support of Retracing Our Roots! This is local programming at its best—keeping our community connected through shared history. We couldn’t do it without the generosity of businesses like Rapp’s. The next time you’re in Mountain Home, be sure to stop by Rapp’s Barren Brewing Company and thank Russell Tucker and his amazing crew for their support. Sip – Savor – Sojourn – Retracing Our Roots.

If you have any topics or ideas you'd like to hear about, drop us a message!